Douglas M. Costle: Oral History Interview

Foreword

This publication is the fifth in a series of interviews of EPA leaders that includes William Ruckelshaus, Russell Train, Alvin Alm, and William Reilly. The EPA history program undertook this project to preserve, distill, and disseminate the main experiences and insights of the men and women who have led the Agency. EPA decision makers and staff, related government entities, the environmental community, scholars and the general public will all profit from these recollections.

Separately, each of the interviews will describe the perspectives of particular leaders. Collectively, these reminiscences will illustrate the dynamic nature of EPA's historic mission; the personalities and institutions which have shaped its outlook; the context of the times in which it operated; and some of the Agency's principal achievements and shortcomings.

The techniques used to prepare the EPA oral history series conform to the practices commonly observed by professional historians. The questions, submitted in advance, are broad and open-ended, and the answers are preserved on audio tape. Once transcripts of the recordings are completed, the History Program staff edits the manuscripts to improve clarity, factual accuracy, and logical progression. The finished manuscripts are then returned to the interviewees, who may alter the text to eliminate errors made during the transcription of the tapes, or during the editorial phase of preparation.

Biography

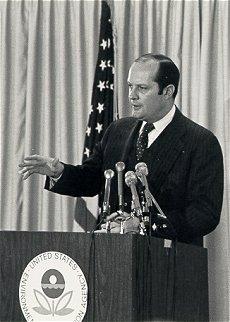

Douglas M. Costle (born July 27, 1939) served as the third Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency between 1977 and 1981. He spent his early years in Washington, D.C. During his teens in Seattle, Washington, he gained an appreciation for the pristine air and water then taken for granted in the magnificent Pacific Northwest. He attended Harvard University (BA in history, 1960) and law school at the University of Chicago (JD, 1963). In 1965 he married Elizabeth (Betsy) Rowe.

Punctuated by stints in the private sector in law offices and urban planning firms, his public service career included positions in the Departments of Justice and Interior, on the Ash Council, as Commissioner of the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, and at the Congressional Budget Office. He subsequently served as Dean of the Vermont Law School. He founded and chairs the Institute for Sustainable Communities, which focuses on building public and private environmental protection infrastructure in the eastern European countries of the former Soviet Union.

Mr. Costle resides in Woodstock, Vermont.

Interview

Early life and influences

Q: To begin with, I would like to get some background on your pre-EPA years. You worked on the Ash Council which created EPA, but I would suspect that your interests in environmental issues were already forming by the time you began working for the Council. Tell me about where you grew up and what or who some of your early influences were, prior to taking on environmental protection as a career.

MR. COSTLE: I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, and my early experiences there probably shaped my awareness of the need for environmental protection. I remember clean air and water. You could fish in almost any stream around the Seattle area.

Q: Did you fish?

MR. COSTLE: My dad and I fished near Mt. Saint Helen's, at Spirit Lake, in fact. I've done more since then, in Alaska, for instance. Fishing was one outdoor influence. Too many people today don't remember how environmental issues became part of the American political landscape. A handful of scientists had been ringing the alarm bell, and then the press picked up on it. The Cuyahoga River caught fire in Ohio. I remember a photograph on the front page of the New York Times captioned "The Skyline of New York." It was as if the negative was faulty, because the smog was so dense. Very few people could define the word "ecology." Now every school child can. There has been a profound change in our political value system. Growing up in the Pacific Northwest, you almost took for granted that the air would remain clean and the water fishable and swimmable -- the goals stated in the '70 Clean Air Act and the '72 Clean Water Act.

Q: So the degradation that people were seeing by 1970 was, perhaps, a slow accumulation, but it became profoundly manifest in the late '60s.

MR. COSTLE: Exactly right. "Earth Day" in 1970 was a very significant political event, but its founders would tell you that they could never have organized it if the time wasn't right. In American political life, timing is everything.

Ash Council and creation of EPA

Q: You served as staff to the Ash Council, which created EPA. Who brought you onto the Ash Council?

MR. COSTLE: A friend named Amory Bradford, who had once run the New York Times and served in a variety of federal positions over the years. After law school in the '60s, I had joined the Department of Justice (DOJ) and been assigned to the Civil Rights Division. The previous summer, in '63, I had worked for Justice, with the FBI in Mississippi. I photographed public records and interviewed witnesses in the early suits over the use of literacy tests to disenfranchise blacks in the South. These suits led to the '65 Voting Rights Bill, which fundamentally changed Southern politics. I was just a young law clerk, and my only identification was a letter from Robert Kennedy saying I worked for the Department. This probably would have been enough to get me shot if I had ever had to show it to anybody. Right after the Watts riots and the Newark fires, Amory was with the Economic Development Administration (EDA) in the Department of Commerce, and he thought Oakland would be the next tinderbox. He wanted to take the jobs creation potential of the EDA to Oakland to see if that could make a difference. Then came the Ash Council.

Q: What were the purposes of the Ash Council, and what were the Nixon Administration responses to your proposals regarding EPA? The Council wasn't entirely successful, or at least many of its proposals didn't go through. Yours was one of the few that did.

MR. COSTLE: Basically, two proposals succeeded: the creation of OMB (Office of Management and Budget) and the Domestic Policy Council (DPC), and the creation of EPA. The Ash Council looked into making EPA part of a larger department and ultimately decided not to.

To give you some background on the Council, one of the first things that every president since Roosevelt has done when taking office is to set up some sort of commission to look at federal government organization. President Nixon's council, formally named the President's Advisory Council on Executive Organization, consisted mainly of very successful business people who ran large organizations. For example, Roy Ash, the chairman, was head of Litton Industries, a very large and successful firm that did a good deal of government contracting. The council members were concerned with consolidating the number of agencies that reported directly to the President. They believed the President needed a policy staff, because their perception was that Cabinet officers often became captive of the "iron triangle" of the executive, legislative, and lobbying communities, whose interests were not always those of the President. A White House staff that was a mixture of career policy specialists as well as the President's political staff would serve as a small think tank to help the President sort out policy debates and choose options.

The Bureau of the Budget didn't like this proposal because it had traditionally played this role, and the Cabinet didn't because the members saw themselves as the President's staff. They feared that the Ash Council's proposed Domestic Policy Council would interpose itself between themselves and the President.

In the midst of all this, Amory's staff was grappling with improving the organization of the government's myriad programs dealing with the environment, ranging from managing public lands to mineral leasing and extraction, anti-pollution programs, power generation, and the regulation of pesticides. These functions were scattered throughout the Departments of Interior to Agriculture to HEW (Health, Education and Welfare) and independent agencies. This executive branch fragmentation of authority was mirrored on Capitol Hill, among all its different committees and subcommittees. The Council's predisposition was to lump all these programs into one new cabinet department.

I was convinced that idea would not fly. First, it would require legislation, because the President's reorganization authority did not extend to creating new cabinet departments. Although Congress had to approve any plan to transfer programs from one department to another one already existing, such a plan would automatically go into effect unless Congress actually vetoed it. And the larger and more complicated the plan, the more likely a veto would occur. Second, no matter how neat, streamlined, and sensible a proposed plan might be, it would be torn into pieces on Capitol Hill by all the interest groups. While everybody talks about how protective the bureaucracy is about its turf, it's not basically the bureaucrats. In the end, the civil service does not have much power itself. Power lies with the Congress and the interest groups, often aided and abetted by the bureaucracy. Congress and the interests resist change because -- the minute power shifts -- loss of control or influence plays its way through the bureaucracy, the press, the political process. I remember the admonition: "If you send a racehorse up to Congress, it is sure to come back into the tent looking like a camel."

A reorganization plan, on the other hand, would not be subject to amendment. It had to be voted up or down as submitted. The Ash Council members, however -- being very smart businessmen but not necessarily smart Washington operators -- thought the logical step would be to combine all the federal environmental, energy, and land resource programs in one cabinet department, presumably Interior. This would be the first major Cabinet shake-up.

We staffers were instructed to brief each of the Cabinet members who would be affected, nine out of ten of whom would lose something. Each Cabinet officer made a pitch for placing the new entity in his own Department. Even the Army tried, saying, "The Corps of Engineers needs a new mission." But Russ Train, who had then just been named chairman of the new Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), was the first to argue that EPA ought to be independent. He believed that anything else would not be seen as a fulsome response to the growing public perception that environmental problems were getting out of hand and that a highly visible and focused response was required.

Roy Ash reasoned that the standard-setting and enforcement functions of an EPA really needed to be informed by all the Cabinet perspectives: urban, agricultural, commerce, health, natural resources. He toyed with the idea of a coordinating council and became persuaded that it just wouldn't work. The rule in Washington is that everybody wants to coordinate, but nobody wants to be coordinated. So the Ash Council endorsed the idea of a separate, independent EPA reporting to the President. They did not seriously consider a commission form like the FTC (Federal Trade Commission) or the ICC (Interstate Commerce Commission), regulatory agencies set up primarily for the economic regulation of industry, which were as much creatures of Congress as of the Executive Branch.

Using a reorganization plan was brilliant, because necessitating a congressional veto changed the dynamics considerably. It meant Congress had to organize to defeat the plan within 60 days. In the end, Congress couldn't muster the opposition. Bill Ruckelshaus, who was then at Justice as an Assistant Attorney General, was named administrator one week before the EPA's effective date of December 2.

Organization of EPA

Q: Did you develop a relationship with Ruckelshaus and Train, before becoming EPA Administrator?

MR. COSTLE: Once the Ash Council delivered its recommendations, Russ became the point man on the Hill, and I in effect became his staff. I knew Senator Muskie and his people at that time, very casually.

I really remember this period as having a flavor of the New Deal about it. This was a new area of public policy, one where government intervention was clearly going to be required. Muskie, to his great credit, supported it because it was the right thing to do. He said, "I'll probably criticize you for not putting enough resources into it. But I'll help you get it through." And he did. He was a statesman, the likes of which there are too few today.

We looked at organizing EPA functionally, that is, around operations like research, enforcement, contracts, etc. But this would involve breaking up the traditional air and water organizations, and we didn't think that would be a practical alternative on Day One. There was likely to be high-level resistance on the Hill, particularly from the House, where it was a committee jurisdiction issue. John Blatnik had to see a water program. Paul Rogers and the Health Committee people had to see an air program. The Senate was easier to deal with in that respect, because it already had a more consolidated jurisdiction in the Senate Public Works Committee. But within EPA we did propose some cross-cutting functions that would begin the process of program integration, such as policy, research, and enforcement.

Our other organizational decision was to establish a very strong regional presence, using the ten standard federal regions to create a rational field structure for EPA.

Q: As you watched EPA develop after Ruckelshaus took office, and as former State EPA head in Connecticut, on the receiving end of what you had developed, how did your vision for the agency change -- or did it?

MR. COSTLE: EPA's initial focus was on the basic organic statutes that it inherited, essentially for air and water. But it was to a large extent in a state of crisis management. You could imagine what it must have been like during the New Deal, when the government was creating whole cloth out of new ideas, programs, law and infrastructure. There was a constant process of legislative innovation. Russ Train had a very strong operation at CEQ, with some extraordinarily bright and capable people like Al Alm, Terry Davies, and Bill Reilly. They saw themselves as a fountainhead for spinning off new ideas and legislative proposals.

Becoming EPA Administrator

Q: How did you become EPA Administrator?

MR. COSTLE: I know only some of the story. I went to Connecticut, helped set up and run that State's EPA, and eventually headed the whole Department. It was a consolidated agency, including the natural resources management functions as well as pollution control. Even though the EPA piece functioned separately, it began to draw strength from the fish and wildlife and water conservation people. We were definitely beneficiaries of the new federal grant-making authority. We were able to triple our staff and other resources.

The federal Clean Air and Clean Water Acts clearly contemplated State implementation and enforcement. Those laws were brilliantly crafted to get results; their compromise was not in the goals or the standard-setting but in the time they would allow you. The Congressional authors calculated that, as this new pressure was applied to the economy, the safety valve would be in extending deadlines. They knew they had to be clear about the objectives, and they set a degree of specificity that no bureaucracy could mumble away.

But State implementation meant big changes for the States. For example, when I was heading the Connecticut EPA I knew that we couldn't run programs with engineers alone. We had to bring additional skills to bear: lawyers, economists, and communications. It was very exciting, actually, to build an operation where you were never more than an hour away from any problem. This proximity also gave us the advantage of quick feedback on where our proposals would work or not. But there was never any lack of resolve that things were going to change. We wanted to do so intelligently, and we wanted to innovate. We developed the administrative civil penalties program, a very clever concept for which Bill Drayton was the spearhead. Washington deals at an abstract level. In the States, you get down in the trenches with the 50 permits that you are going to issue to the State's largest manufacturing employer.

And you're dealing with the complexity of town governments. They will have to raise taxes. They will have to hold referenda -- and those get beat down periodically. I had threats from mayors to have their garbage trucks dump their loads on the governor's doorstep if I shut their landfills. We did shut some down, and trucks didn't come. But those were searing political experiences.

Those were also heady days. I would characterize that period of the '70s as an era of improvisation, and the state level as a wonderful place to get the experience of implementing a law. It wasn't just drafting a document and throwing it out for a policy debate, casting thy bread upon the waters to see how soggy it gets. We had to make the abstract work. To me, this represents a key principle of public service. It's not a political game. In the end, success is measured by getting something done that makes a difference for the public good.

In any event, here I had wound up, a Democrat working for a Republican Governor, a wonderful man named Tom Meskill, who was very supportive. Then a Democrat was elected Governor, and I got thrown out. I called Russ Train and asked, "Do you have any work that I could do while I figure out what I am going to do with my life?" At that instant, the chief environmental staffer retired from the Domestic Policy Council. Gerald Ford was now President, and Nelson Rockefeller was running the DPC, which the White House was actually trying to restore to the Ash Council's original conception. I agreed with Russ that I would fill the DPC seat while Jim Cannon, President Ford's chief of staff, was recruiting. So for several months I had the young policy wonk's dream, including access to the President.

At that same time, I met Alice Rivlin, a young economist from the Brookings Institute whose task was to set up the new Congressional Budget Office (CBO). Up until then, the federal budget would simply emerge at the end of a Congressional season. The green-eyeshades people at the Bureau of the Budget would add up all the appropriations, with no discussion of the larger context -- surplus or deficit -- and no focus on the out-year implications. Congress realized that it was at a disadvantage and needed the analytical capability to do its own budget analysis in order to keep the executive branch honest with the numbers. Senator Muskie and Representative Brock Adams pushed through the 1974 Budget Reform Act, creating the new Congressional House and Senate Budget Committees and the Congressional Budget Office. CBO was to develop policy options for the Congress, crunch the numbers, and prepare five-year projections for existing and proposed legislation. Alice was charged with setting all this up in a hurry. So I traded my White House access, office, and chauffeur service for a three-legged desk and a roof that leaked in the basement of the old Carroll Arms Hotel to help get CBO started. Then came the '76 election.

Early after Jimmy Carter had started running for the Presidency, he had set up a group, under Jack Watson, to plan the transition should they win. Stu Eizenstat worked with that group, as did Bill Drayton. Based on our Connecticut experience, Bill asked me to prepare a memorandum on EPA, from my perspective as a former state administrator. I remember making a very strong pitch for management, for people who understood these programs, had been involved in their development and implementation, and could tighten up the agency for another era of growth. With respect to rulemaking, I argued that EPA needed to better anticipate impacts and implementation problems.

After Jimmy Carter won, I got a call asking if I would join the transition team, working on government reorganization issues. I talked with Alice about the offer. By that time it was clear that the Congress, at that point, was only interested in numbers, not in policy options -- unless the options agreed with what the sponsor wanted. It was a testy business to get a Hill client to request a policy study of, for example, the space shuttle without also having him suggest the conclusions that were to come out. To her credit and because of her integrity, Alice would not play the game that way, so CBO did not. But I thought this new opportunity would be more exciting, so I left CBO for the transition team, not knowing what I was going to do afterwards.

The Carter transition team was organized into clusters, with one group working on appointments in the environment and energy area: the Departments of the Interior and Energy, CEQ, EPA, etc. Because I had administered a State agency, my name got on the list of EPA candidates. Cecil Andrus was picked for Interior, and Jim Schlesinger for Energy. One morning Cecil asked me to come see him, and we had a wonderful chat for about an hour. I knew he had already chosen his deputy and several key assistant secretaries, and I began to think this had to do with EPA, particularly when he asked if I thought EPA ought to be merged with Interior. I went through my litany of reasons why not. He said, "Good, I agree." I later learned my name was forwarded to the White House, basically because I was the only one of the final four candidates who had run anything sizable.

A short time later, I was asked to meet with Hamilton Jordan at the White House. He asked, "Could you see the President tomorrow?" I went in on a Saturday morning, and the President and I talked well beyond the scheduled 20 minutes. When I left, he said, "I want you to call me directly any time you need to. You should never feel that you can't get through to me. By the way, you'll have to fill out papers for the FBI."

In Ham's office, I told him, "I think I have just been offered a job, and I think it's EPA." Ham roared and said, "That's right."

I liked President Carter personally. He was very bright, a man who clearly was interested in how government worked. You sensed real integrity. He didn't know many details about EPA, but he felt very strongly that this area would be important to his Administration.

Carter Era at EPA

Q: What problems did you have with transition, going to EPA in a new administration, at a time of party change?

MR. COSTLE: I had an advantage in knowing the EPA players, Russ and Ruckelshaus, of course, and John Quarles, who was Acting Administrator, as well as the incumbent Assistant Administrators. I did not know the White House staff, the Jordans, Eizenstats, other Georgia people. The next layer down were largely from some very good Capitol Hill staffs, from Phil Hart's and Muskie's offices. The first thing I did was to see Bert Lance at OMB. OMB and EPA had been at perpetual loggerheads, largely because of the "Quality-of-Life" review set up by OMB. This process had meant, in effect, that everything EPA did had had to be cleared by OMB. I told Bert, "Congress has been placing more and more responsibility on EPA without giving additional resources. The administration did not allow it." With the help of Elliot Cutler, the new OMB assistant director for natural resources, and Kitty Schirmer, we worked out the first major increase in resources for EPA. It was a 15 or 20 percent jump in Carter's very first budget, a wonderful signal to the Agency and the public that environmental concerns were going to be taken seriously in this Administration.

I asked John Quarles about the Quality-of-Life review. He said, "It's awful. Why don't I just opt out and take the heat." John unilaterally stopped the review, with the collaboration of Elliot and Kitty.

President Carter had asked me to consider Barbara Blum as my Deputy. I wanted someone who could deal directly with his personal staff, based on long-standing relationships. EPA administrators rarely bring the President good news, but the White House is always being lobbied by everybody who is affected by the agency. When the Chairman of General Motors calls the White House, they take his call. So Barbara's appointment was good for us.

Ham said I could pick the Assistant Administrators. I probably had a freer hand than any administrator before or since. The overall result was that we had as strong a team as could have been recruited, then or now. It included Tom Jorling, who had written the Clean Water Act, and Dave Hawkins, one of the country's chief environmentalists, who was a specialist in Clean Air Act issues. I had already enlisted Bill Drayton, who had been working on EPA matters with the President's transition team.

For R&D (Research and Development), I decided to look hard inside, and tapped Steve Gage. He had been the EPA R&D representative who had served as liaison to the New England states at the time of the 1974 oil embargo, when proposals to site refineries on Long Island Sound had cropped up. He was very objective and thoughtful. He never winged it, but would say, "I don't know that answer; let me get it." We decided to beef up R&D, to introduce peer review, strengthen the outside Science Advisory Board, create research centers around the country, consolidate the EPA laboratories, and broaden the network of scientists the agency consulted.

By 1977, EPA was under a barrage of incoming mortar rounds. It was under a scientific assault that argued its standards were not solidly based. Some complained that the agency wasn't efficiently getting new programs out, others that it was ignoring the States. Industries were suing; every rulemaking got litigated. When I arrived, a stack of rules was sitting on my desk for signature. I told the agency's General Counsel that I wouldn't sign until I had read them, and he said, "You have no choice. You'll be in contempt of court." Eighty percent of those regulations were there because of either a legislative or court-ordered deadline. The remainder were largely negotiated, often to keep us out of court, or were rules that the parties had all agreed to. It was no wonder that EPA had acquired its reputation for lack of timeliness. The agency was suffering a bottleneck and had not gotten adequate new resources to handle the new laws passed every year.

Q: Some Administrators have used their Deputy as a sort of Mr. Inside. You chose to make Barbara Blum your White House contact.

MR. COSTLE: Barbara and I had agreed that we were going to rely on our very strong team of AAs (Assistant Administrators). She was very effective when we set up cross-agency teams to focus on complex issues. And she also handled a lot of the international work.

Q: Did you meet a lot of internal pressure or stymying to your program?

MR. COSTLE: No. Partly because there was a perception that the outside world was increasingly hostile toward EPA. There was reality behind the perception. Remember, the Nixon years had been years of budget impoundments, Quality-of-Life reviews, efforts to bottle up the agency. Pressure and frustration had been building. There was now a perception of a President and administration that would be sympathetic. People inside and outside the agency were looking for me to solve problems, to demonstrate to the Hill and elsewhere that we were attacking problems aggressively.

Early Objectives at EPA

Q: Is there any way to mitigate that period of lame-duck time, where the flow of paperwork continues, without it becoming a millstone around the next administrator's neck? Or is that just a natural thing that there's no way to fix?

MR. COSTLE: I think it's going to happen. Having been an administrator, I think the last thing you want to do is bag your successor by leaving ticking time bombs. On the other hand, there may be some things you feel it's urgent to do before you leave, because they are part and parcel of what you consider your administration to be about. Given EPA's always intense, full workload, some throttling down may take place, but inevitably it's still a busy place. You may be able to mitigate some of that. The earlier you know who your successor is, the earlier you can start working with that person. That can make transitions easier.

I had a clear first set of objectives: Recruit the AAs and stabilize the agency. Take charge of the flow so the staff felt that they weren't spinning their wheels. Get on top of the critical legislative battles over the '77 Clean Air and Clean Water Amendments. And cutting a budget deal that provided additional resources, even before I got there, served as a signal that our new team wasn't simply a boarding party.

Another of my goals was to continue to build the state government infrastructure. EPA could never be everywhere; we needed to leverage our limited resources. By 1977, it was clear that dealing with environmental problems would be an ongoing, steady government responsibility. Building the national infrastructure to cope with that was essential.

Q: In hindsight, could the agency have done anything to make your transition smoother?

MR. COSTLE: The Agency was terrific. John Quarles was terrific. If I asked for information, they served it up. The pending Clean Air Act Amendments were complicated, and we had to rapidly formulate an administration position. We were really forced to rely on the career staff. One thing I had learned in Connecticut was that career people are an extraordinary resource. You not only ignore this at your peril, but you are foolish in the extreme if you don't take advantage of their knowledge and understanding. You still have to bring leadership and, ultimately, your own public policy choices. But if you don't harness yourself to the agency and its skills right away, you lose. You have to ask the right questions. You will find some career people who have, for whatever reason, a rigid point of view. But I remember the agency being eager to help, and I was eager to have that help. Besides the budget increase, I had worked it out with President Carter that I would attend Cabinet meetings and be dealt in on key administration decisions from which Russ Train had been shut out. So the staff felt hopeful, and I think they were pleased with the caliber of AAs that we very quickly announced.

I recruited Steve Jellinek from CEQ to run the new Toxic Substances program. Along with the appointments of Drayton, Jorling, Hawkins and Gage, the signal to the career people was that this team had been on the barricades with them. Dealing with the agency internally is like dealing with the White House. It's a bank account on which you are always making withdrawals. Every day you send the White House bad news, so you'd better make healthy deposits along the way so you keep a positive balance in your account. The same with career staff: you are not going to get the best from people if you are beating up on them. They need to feel that you appreciate what they do, that you respect them for what they know and bring to the discussion. In return, they expect you to lead, to be decisive. They are not going to begrudge losing this or that bureaucratic battle as long as they think it's been a fair game.

My father-in-law had been one of FDR's (Franklin Delano Roosevelt's) young bright assistants. He told wonderful stories about the New Deal: the excitement, the fact of breaking new ground, the camaraderie, and the sense that what they were engaged in was of great national purpose. I think that EPA's first full decade was about as close to the spirit of the New Deal as you can come.

Q: So you had an FDR model?

MR. COSTLE: Not in any formal way. But I remember looking at resumes we were getting for the General Counsel's office. They'd knock your socks off. When talented people really want to do something like this, which usually involves some sacrifice, that's a terrific sign. Good people always have somewhere else they can go.

Role of Regional Administrators

Q: You had to place a lot of trust in your regional administrators.

MR. COSTLE: Yes. I wanted strong regional administrators, a mix of career and outside people. And President Carter also agreed it was time to break the glass ceiling, so we carefully searched for women with experience and capacity. The regional offices were wonderful training grounds. And we moved Deputy Assistant Administrators around to get experience in other media programs and begin to see the agency more as a whole.

Turning attitudes around on the Hill really worried me, because the bitterness and anger that I ran into during my confirmation interviews were palpable. Remember, we were dealing with the post-Watergate Congress, with many new members without federal experience, many more subcommittees, and a somewhat hostile attitude toward the Executive Branch. And at that point, Congress was at a stalemate on amendments to the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. I recruited our legislative director, Chuck Warren, from Senator Javits' staff. We prepared a chart of appearances before Congress by Russ Train and his AAs. Wherever we displayed it, everybody grasped the extent of the interactions between EPA and the Congress. These became much more extensive with the House's reorganization, when it seemed like every member chaired some subcommittee, with each drawing a bead on EPA.

The truth was that the Agency was still innovating and improvising. This would never stop with the signing of a particular bill or regulation. Our understanding of the nature and scale of environmental problems is so much more sophisticated today than it was then. We hit EPA right at the time when its learning curve was coming right up against the political resistance curve.

Q: How would you characterize the relations between the regions and headquarters?

MR. COSTLE: There's always an inherent tension. You want the regions to be close to the States, to give the day-to-day attention to state programs that headquarters can't. But if you just turn all ten regions loose, you'd have chaos. So you always need a balance between national guidelines and enough flexibility to meet the problems in the field. Our innovation of RA (Regional Administrator)/State Agreements -- which required fifty programmatic, across-the-board renegotiations each year -- gave us a chance to recognize individual differences and priorities. I repeat, there will always be a certain tension, but it's how well you mange it that is important.

Vision for EPA

Q: How long did it take before the decisions coming across your desk bore a stamp of your vision of the agency, as opposed to being the legacy of previous policies?

MR. COSTLE: Probably two years. It takes time to influence that stream, because decisions work their way up over a considerable period of time. But this doesn't mean we didn't make an immediate imprint. We first identified the twelve most important, most controversial proposals and intercepted those to make sure we could shape them. But it wasn't until we had the first good regulatory calendar in place that we could set up a thorough review system that worked. By the time I left, I felt comfortable that there were no surprises in the pipeline. But this still didn't obviate day-to-day crisis management. This constant queuing of urgent matters can overwhelm your calendar if you're not careful. You have to fight to set priorities and ensure that the things you want to focus on get to you in a timely way.

Congressional Relations

Q: You certainly had some heavyweight Congressmen on your side, but you were then about to lose Senator Muskie, the environmental statesman who had been such an agency ally. How was your relationship with Congress?

MR. COSTLE: Personal interactions are important. My approach was to level with them. You want them to walk away from a meeting with the impression that they have dealt with somebody who is professional, thoughtful, who understands their problems. You have to invest time and energy. To a surprising extent, the enterprise is very personal.

Q: The '74 class in Congress was increasingly populistic. That tendency has only grown since that time. How did you handle the degree of populism and the sort of anti-bureaucratic tone that came in with it?

MR. COSTLE: You have to play straight. In the long run you gain by doing so. We worked very hard to build EPA's credibility. A regulatory agency cannot be partisan, and EPA had always had very strong bipartisan support. As the going got tougher, this was more and more important. Of course, we didn't win them all. We got beat up pretty good a couple of times on the Hill, and many times no amount of professionalism would have saved us. One example was the auto emissions issue. The auto industry was John Dingell's constituent, and he was going to protect it. But the caliber of our people, and the quality of the debate we tried to maintain, was such that we more than survived our watch.

That turned dramatically with Anne Burford and resulted in subsequent bipartisan legislation that put a straitjacket on EPA. In many ways, the agency lost its most important asset, its flexibility. That's why reforming EPA today is going to be tough. We are again in a polarized and very much more partisan environment. The notion of Congress giving the EPA Administrator flexibility to improvise is not popular. Congress today tends to specify detailed requirements without always knowing the consequences.

True, we never published a rule where we could honestly say we knew all the consequences in advance. But we always tried to build in enough flexibility so that we could use common sense in implementing down the line. For instance, we had to change the ozone standard. It had been based mainly on one study, which turned out to be flawed, but nobody wanted to touch the standard. The pressure from the Hill and environmental groups was extraordinary. Yet, I couldn't justify the standard on the evidence; it would have been more costly to our credibility. In the end, you govern by consensus. Every administrator is always going to be in the middle of a bull's eye and had better be concerned about credibility.

Press Relations

Q: It seems that the press is very important in that regard.

MR. COSTLE: When I became administrator, the national environmental press was represented by four publications: the Washington Star, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal, and the New York Times. I asked their reporters about finding a chief press officer, and they all basically told me the same thing: "You have somebody now who is really good, Marlin Fitzwater." He and I developed a wonderful working relationship. Every day he earned the respect of the press. He never permitted the agency to mislead or misrepresent.

Q: Did you ever find yourself using the press against Congress or trying to mobilize public perception?

MR. COSTLE: Never against individual members of Congress. But we did try to capture the high ground of public opinion. The press plays an absolutely critical role for the agency in our modern communications age. But you don't manage the press. You manage your own actions, with an awareness of how the public and the press are likely to perceive what you're doing. If the public doesn't know the issues, doesn't understand them, or isn't concerned about them, then you've got trouble. The other side of that coin is that you never run around yelling fire in a crowded theater. That's irresponsible. So did we use the press? Yes, in the sense of making sure the press knew what was going on.

One of the risks, obviously, is that press coverage can cause something to spin out of control. An example of that was the premature release of the Love Canal chromosome study, before it had been peer-reviewed. I think that directly contributed to the subsequent panic. Whose fault is that? The press? I can't say that. It was newsworthy. But whoever leaked the information in the first place was irresponsible.

Q: Do you think the press had the level of sophistication, at that time, to understand things like peer review?

MR. COSTLE: Perhaps some of the smaller papers didn't, but some did: the New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, the former Washington Evening Star.

Q: Did you find yourself using the press, even in subtle ways, against the administration, or against some part of it such as OMB?

MR. COSTLE: I never looked at the press as an agent, because the press would never willingly be anybody's agent. If reporters thought you were trying to use them, it would be the fastest way I can think of to burn your bridges with them. My rule was that you are doing the public's business, and you do the maximum amount of it in public. Sometimes, of course, agency staff has to meet in private to decide what they are going to do. Those discussions need to be free and open, without fear of repercussion. But I felt that in the long run that doing the public's business in public view would serve EPA's interests. We might not make everybody happy, but we were trying to do our job, and we'd have to stand or fall on that.

Relations with OMB

Q: Were you ever frustrated by OMB not having to play by the same rules?

MR. COSTLE: Oh, sure. That makes OMB as tough as nails to deal with. But I have to say that, during my time there, EPA probably had more parity in bargaining than most other administrations have enjoyed.

Q: Because of your allies in OMB?

MR. COSTLE: Initially because of allies, but other things we did helped in the long run. For example, we were the first agency to volunteer for zero budgeting. The staff moaned, but I argued, "Think it through. We look at our base and set up a rational system for establishing priorities. We essentially take away OMB's role. I will be able to say to the President, 'After we have gone through this, are you going to let those little gremlins change and re-rank priorities?'" This is a somewhat over-simplified explanation, but it pretty accurately describes what actually happened. We basically won our battles.

Environment and the Economy

Q: How did you handle the economic realities of the recession, with people in industry and other public arenas saying that environmental regulation was strangling the economy?

MR. COSTLE: Much of that was overstated on their part. My approach was to assemble the best economic staff I could and take industry critics head-on. I asked Bill Drayton to do a study of the five most expensive rules that EPA had ever adopted. I wanted a comparison of agency forecasts of the likely expense of compliance with industry's forecasts and with the actual costs. The results were very interesting. In four of the five cases, both the government and industry had significantly overestimated the actual costs. In one case, both industry and government underestimated the costs by a magnitude. In the four cases where we overestimated, our costs were closer to reality than industry's. And where we both underestimated, again our figures were closer to actual costs.

But when you are prospectively estimating the impact of a proposed rule, you are dealing with models and assumptions. Reasonable people can disagree; people with an interest may deliberately disagree. Also, it is easier to estimate costs than benefits. Industry uses very conservative cost models that tend to produce larger numbers.

In estimating, if actual costs are less, you benefit. But the fact that you have used the conservative models gives credibility if the costs turn out to be lower. In some instances where there was going to be controversy over major rules, we had OMB and the White House convene the agencies involved to agree on models in advance, so there would be no subsequent argument about assumptions.

I believed that the most important thing was to get facts on the table. My motto is, "Facts are friendly." People with different political philosophies can come to the same problem and reach similar conclusions, unless they are ideologues.

The White House is never going to be able to do its own analytical homework. It would have to re-create the government to do so. On one of our biggest rulemakings, we went to the White House staff and decided on the models ahead of time. We got the other agencies -- DOE (Department of Energy), DOT (Department of Transportation), OMB, the Council of Economic Advisors and the Council on Wage and Price Stability -- to agree. As a result of this process, we were never vulnerable to lawsuits alleging that we had been told what decision to make.

One example of this came with the auto industry. Toward the end of the administration, foreign automakers were having Detroit for lunch. The five top company CEOs met with the President; I was the only regulator there. The automakers were seeking five specific forms of relief, including regulatory relief. One CEO said, "Mr. President, do you realize that twenty percent of the cost of every new car is the cost of meeting federal regulations?"

President Carter asked, "Is that so, Doug?"

I said, "It is, Mr. President, but you have to look at that number carefully. Eighty to eighty-five percent of it is the cost of meeting Congressionally-mandated fuel economy standards. If you were to add up all the health, safety and environmental requirements, it's about three percent of the cost. Some argue that figure is much too high; others that it's too low."

At that point, Lee Iacocca said, "Mr. President, the fact is, we blew it. The industry is making the wrong kind of cars. We let the imports steal our lunch. We need to retool, and we need to buy time to do so. We need relief, but I put regulatory relief fifth on a list of five." They moved on to discuss import quotas and other items. And that was that, but I knew when I said what I did that OMB wasn't going to contradict it, nor was the Council of Economic Advisors. Maintaining this level of credibility meant you had to be really conscientious about making sure your facts could stand up.

Q: How often did you find yourself standing up before the President, OMB or others, and saying, "But I can't do that, because Congress has mandated that I do something else?"

MR. COSTLE: By the time issues got to that level, we had worked very closely with the White House staff and others. You don't rub their faces in it. That's counterproductive. So the situation never came up in the way this question is framed. But personal relationships also make a huge difference. Over time, you build up trust, which becomes very important. I think it has made a difference to EPA throughout its history, with people like Ruckelshaus and Train, Bill Reilly and Lee Thomas and Carol Browner. You cannot ever afford to undercut somebody. It is one thing to win or lose on the merits. It is another to use shady methods or not do your homework. Once you lose your credibility, you're dead, absolutely dead.

Regulatory Analysis

Q: With regard to the White House and OMB, what were your perceptions of the Regulatory Analysis Review Group (RARG)?

MR. COSTLE: Presidents have a legitimate concern about how regulatory agencies behave. There were legitimate concerns about the cumulative effect of regulation. Regulation was becoming a bigger and bigger function of the federal government. Government no longer just defended us, built ships and flew planes. It told the private economy how to behave on certain matters, from child labor to environmental protection. And nowhere was there a single source that would tell what was coming down the road from the plethora of federal agencies, or what the cost might be.

Then there was the matter of coordination. Three or four different agencies regulated lead. Was there consistency in what OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration) and EPA were doing? Was OSHA cleaning up the factory floor only to push the lead out the smokestack into the ambient environment?

Although the issues were legitimate, the regulators themselves tended to see outside questioners as standing in the courthouse door. And, in fact, the White House under previous administrations had been largely unsympathetic to regulatory agencies. OMB had been used to create a choke point. In the Nixon years, the White House was very responsive to big business interests. That said, however, realize that business interests are going to make themselves heard in any White House. They have the clout to get an audience. How much sympathy they get is another matter. We were dealing with a White House that was more sympathetic to us than to the industry that was crabbing about us.

Q: On issues such as lead, did you try to win more coordinating authority for EPA? If you had three different agencies regulating in a particular area, did you see EPA as needing to be the primary agency on those issues?

MR. COSTLE: As I said, in Washington everyone wants to coordinate, but nobody wants to be coordinated. Neither industry nor environmental groups are averse to pitting one agency against another. I argued that the right way to answer legitimate questions was to have the regulators themselves advocate for competent reform. Rather than cede veto authority to the White House -- which was legally questionable and could lead to litigation -- I persuaded the White House to create a regulatory council, a forum in which the regulators themselves could address the issues. I further suggested that everybody develop a regulatory calendar, so that we would have a central place to learn what was coming down the road. So I viewed RARG as legitimate Presidential oversight.

I found that the RARG staff asked good questions; they were largely sympathetic. Even the economists realized we had a job to do. A major problem with the economics point of view is that it can easily be perverted into a prescription for doing nothing. In some respects, economics holds out false hopes of introducing a level of certainty that simply does not exist in reality. Nobody would argue against the use of cost/benefit analysis or quantitative risk assessment to help organize the limited data you usually have. But when it gives the false sense of security that decisions are certitudes rather than judgment calls, I think it serves ill purposes rather than good.

RARG's effect on rulemaking, if any, was probably to sharpen us up in doing our homework. We were never contravened. I always conceived of my job as representing the President, and I was never instructed to do anything different than what I was proposing. Of course, knowing RARG wasn't just a hit squad trying to throttle us made a huge difference between the way the Quality-of-Life review and RARG were perceived.

I also started the Interagency Regulatory Liaison Group (IRLG), involving EPA, FDA (Food and Drug Administration), OSHA, and the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). We analyzed all the research being done under the auspices of each of the agencies and discovered it was like a piece of Swiss cheese. There were important issues that none of us were looking at. We told OMB, "If you want better regulation, you'd better fund the science research." But OMB gummed the bullet; it didn't have the brass to tell NIH (National Institutes of Health) to start paying more attention to serving the regulators' needs.

Although it fell apart when Reagan took office, RARG was a worthy effort. The process was designed to create a cooperative environment among the regulators and to address issues, particularly economics, without the kind of political tension that had existed and has now emerged again.

One of the legitimate concerns that I and other regulators had with RARG was -- while it's one thing to deal with a Charlie Schultz, Fred Kahn or another broad-gauge, largely sympathetic person -- it's quite another to deal with an ideologue like a Dave Stockman. Whatever arguments the former might have had with basic statutes, they understood what was involved. More than anything they wanted to be assured we were using good judgment. There was, however, always the risk that a bureaucratic apparatus would rise up underneath and become arbitrary. Fred was once embarrassed when we found his staff just cutting and pasting industry comments and sending them to us on official letterhead.

With OMB, I think it is, and always has been, a power trip. OMB tells agency heads, "We've got the authority of the President to tell you that you can't do this." OMB staff work for the President, and do what -- they claim -- the President wants them to. But in reality, they create that. Agency heads always feel caught between OMB and the statutes, like the salami in the sandwich. Still, we had a better time of it than most, in that the OMB assistant director who had EPA oversight had had Hill environmental experience, on Muskie's staff. We also had allies like Kitty Schirmer on the Domestic Policy Council staff. Above all, we had a President who believed in what we were doing. But there's always a concern in the White House that EPA may do crazy things, a perception fed by industry and other people for their own purposes.

Q: Was that perception also generated in part by some of the early EPA staff? Lone Rangers whom people looked at as environmental fanatics?

MR. COSTLE: Industry and others, looking in from the outside, easily see hobgoblins where none exist. And the stakes were high. Opponents could afford to hire the best lobbyists and batteries of scientists. But I think industry attitudes began to change. More and more, industry accepted that EPA was here to stay.

Improvisation does not end when the ink dries on a new law or a new regulation. Laws are not written in stone, and EPA has to keep faith with the Congress. If we were going to carry any case for reform back to Congress, we had better be able to demonstrate a good-faith effort to implement the laws as written and have some empirical basis to suggest that there was a better way.

In sum, the Regulatory Council was set up to address what we all agreed were legitimate concerns: the cumulative burden of regulation, the cost-effectiveness of regulations, the coordination of regulatory interventions, and the quest for a better-articulated research program. Everybody bought into these objectives, whereas -- had the White House simply issued executive orders to the same effect -- the natural bureaucratic instinct on any agency's part, with its own constituencies and Congressional committees behind it, would have been to stiff them, to find a way around: resist, resist, resist.

Just sharing information was worth the effort. OSHA and FDA were trying some new things in rulemaking; so were we. Without the Council, we would have had no organized way of finding out what was working in other agencies that might work in EPA. To this day, I regret that the Reagan administration didn't bring in serious students of public administration, who would have seen the problems and how we tried to deal with them. I think in many ways the Reagan era wrecked the opportunity for real regulatory reform for a number of years, because future attempts would be perceived as regulatory retreat. In fact, President Bush's theme of regulatory relief was an unfortunate characterization that just polarized everybody. I believe that the problem persists today, only the polarizations and misconceptions are on the Congressional side rather than the executive.

EPA Legislative Involvement

Q: How important to your mission was crafting drafts of legislation during your tenure? Or did that happen?

MR. COSTLE: Oh, sure. If you have a relationship of trust with the Congress, they really want your input. You have to implement the law so, theoretically, you have a right to be at the drafting table. Again, it is a process of give-and-take. In our system, the legislative process at its best is even more give-and-take than is rulemaking.

Q: How much of the wording of TSCA (Toxic Substances Control Act) and Superfund was EPA's and how much came from Congressional staffs?

MR. COSTLE: It's really hard to allocate. But the only time you worry is when you're not part of the process. Usually a member of Congress doesn't want to go with something that the agency says is nutty. At least, it used to be that way. Nowadays, the [1994] Congress is altogether different.

On one level, I'm not surprised that efforts to undo environmental legislation bogged down this year [1996]. I think the new Republicans went way beyond any mandate they had. I really believe it has been tragic that such partisanship has taken over, and I think it's one reason that many of the moderates of both parties are leaving.

EPA and Science

Q: How did you deal with Congress about the debate over science between EPA and industry?

MR. COSTLE: After the 1977 battle over the Clean Air Act, it was clear that, if you couldn't get a friendly set of facts in front of the Congress, you couldn't ever get a healthy resolution of the debate. The '77 Amendments called for the auto industry to perform a ton of research, and the industry geared up to do defensive research. At the same time, funds for public-health-oriented research were diminishing. I worried about that trend and said, "What if we created a non-profit, independent institute to do emissions research? Then the next time we come around to reauthorizing the Act, there will be an independent, third-party source of facts."

Senator Muskie was not happy with that idea; he believed in his gut that the research ought to be government-funded. I was more worried that government was losing credibility in people's minds, so that its research wouldn't have the same clout as in the past. In the end, Muskie agreed, and we created the Health Effects Institute, with Archibald Cox as its first director. As the victim of the Watergate Saturday Night Massacre, Cox was probably the one name in the country that everybody knew who was considered to have integrity.

The Institute was created as a non-profit corporation, with the auto industry putting up half the money and us the other half. This approach has provided an effective arbiter of facts, and today you don't hear as much debate about that area. Everybody can argue about the policy options, and this is where the debate really ought to take place.

Q: Is this the same idea as the Environmental Institute that the came from the Ash Council?

MR. COSTLE: No, that was less science- and more policy-oriented, asking: "Are there other ways to skin this cat? Is command-and-control the right way to go?" It's clear to me that command-and-control was the right way to go initially. I don't think there is any doubt. Otherwise, we wouldn't be where we are today in terms of clean-up progress. You need only look at Eastern Europe to see where we might have been without environmental controls.

EPA Policy Development

Q: Who helped you craft those more flexible kinds of plans?

MR. COSTLE: Bill Drayton and his staff served as the intellectual sparkplug. Not that they could develop it full-blown out of a seashell; they had to work with the air and water people. Bill's job, in part, was to challenge.

In EPA's early days, the intellectual power was in the program offices. Gradually, it had become concentrated in the policy-planning shop. I wanted very strong AAs who could regenerate the original capabilities. But I told them, too, that while I wanted strong program offices, I was also going to have this other shop that was going to be just as tough. Out of that, we'd get a better, healthier debate.

It worked that way. It meant it was rougher for the AAs because they sometimes had to battle vigorously with their colleagues. But I was fortunate enough to be able to have Jodie Bernstein, our General Counsel, act as mediator for a lot of the debating.

Another trend that had crept into the Agency during its first years was that the lawyers had become a dominating influence. There was a tendency in the different legal shops to meddle in policy choices instead of hewing to roles as lawyers. I told them, "You're welcome in the policy debate, but you're lawyers first of all. You need to be the best, because we'll be forced to litigate every time we turn the corner. But I'm not going to let you take over the policy process." So we tried very hard to strengthen the media programs and to develop a very good economics and policy shop.

Q: As you crafted these policies that relied less on command-and-control, how did the environmental community respond?

MR. COSTLE: They were nervous and skeptical. But there was really nobody who would argue with Dave Hawkins' or Tom Jorling's environmental credentials.

The environmentalists are not always totally right. They are advocates. If you are a public administrator, your job is to balance legitimate competing interests. Overall, you're an advocate for the environment, but your decisions have got to be informed by a multiplicity of perspectives, within the confines of the law. Flexibility in the law can be an administrator's greatest friend -- the lack, his greatest enemy.

So the environmentalists knew their role was to advocate. They knew that General Motors and the steel industry were in there making their case with all the lawyering and science they could buy. But I think the environmentalists had been very clever in influencing Congress in drafting the Clean Air and Clean Water Acts. They knew they could never match the resources of industry in research and dollars, so they put much of their focus on the process of rulemaking, and access to that process, in order to advocate.

In the end, though, neither the environmental nor the business community is accountable for results. The Agency is, and the Agency has to respect the facts and the law.

Significant Issues at EPA

Q: What were the biggest issues you dealt with as administrator?

MR. COSTLE: I think, first, the power plant standards were high-stakes poker for the whole administration. I am very proud of the way we handled that, and I think it made us all feel we knew something about public administration when we were done.

Q: Why?

MR. COSTLE: Because within the Administration that was the cleanest debate on the merits on the record, and the least politicized. It was politicized on the Hill, but that was inevitable.

The ozone standard revision was very tough.

Responding to Love Canal and choosing the Oil Spill Contingency fund as the model for Superfund, because it allowed the government to take action and sort out the liability later. Getting Superfund through after the election, in a lame duck Congress, was no small accomplishment. There were some good, tough battles inside the Agency over how to implement Superfund. The Washington staff tended to prescribe how the entire program would be implemented. There was too little Washington appreciation, in my judgment, of the diversity of the problem. I think Superfund implementation has probably hurt EPA in the long run, because it was so Washington-focused. The irony was that Burford played right into that. But it would have been a tough statute for anybody to implement under the best of conditions, because it is a tough problem.

EPA and Politics

Q: Was there something inherent in the party politics, not just daily practical party politics -- something philosophical that perhaps led Democrats to look to more decentralized kinds of approaches, whereas Republicans took a more centralized approach during that late '70s, early '80s period?

MR. COSTLE: Leaving aside the question of Democratic or Republican philosophies, I will say this: Many times we would get petitions at headquarters for rulemaking from industry or environmental advocates, on the grounds that they would rather deal with EPA in a single setting in which they knew how to operate, i.e., Washington, rather than have to deal with 50 States. So I think if there is a bias towards centralized government in rulemaking, it is because the affected parties think it is to their advantage.

This may be changing today because of the generally low regard with which government is held in the public mind. The radical Republicans may have temporarily won the PR (Public Relations) wars, saying, "Government is bad and big government is worse. Federal government is the worst, and Washington is the source of all your problems." We are probably going to have to muddle through this stage until people realize that, if you didn't have federal government, you'd have to invent it. The States couldn't possibly set standards for the auto industry. They wouldn't know how to do it, nor would they have the technical resources. But for other issues -- and contrary to what some people argue today -- I think that the original conception of the Clean Air and Water Acts was strategically more clever than people acknowledge. The laws recognize that there are some things the States can do better, frontline enforcement being one of them.

TSCA and RCRA

Q: How would you characterize the Agency's implementation of TSCA and RCRA (Resource Conservation and Recovery Act)?

MR. COSTLE: Both were new laws, and I moved very shortly after I arrived to start implementing them. Tom Jorling was caught up with the '77 Congressional debates, as was Hawkins. Both the air and water bills jammed up, and our first big political crisis was breaking them free. But change, even with a willing bureaucracy, doesn't happen overnight. It is incremental; it takes time to imprint your styles and ideas.

About that time, Tom was headed back to Williams College, and Chris Beck, who had been Regional Administrator in Region II, became AA for Water. It was Chris who alerted me about Love Canal. He had dedicated a new research ship on the Great Lakes, and on his way back he stopped to take a look at what he termed "a little place called Love Canal." He called me that night and said, "Do we pull the plug and let this hang out, or do we try to control it?" I said, "Pull the plug. The sooner everybody knows about this, the better." And it just blew up.

Love Canal

Q: Looking back on it, would you have pulled the plug and let the media, without any sort of spin doctoring, do their thing on Love Canal?

MR. COSTLE: Would I try to spin it? I don't think so. I think this was an issue that the public needed to learn about from third-party sources. Remember, we were discovering the issue at the same time the public was. We knew that it would be a crisis. But it would also remind the American people that the Agency's mission wasn't just about flowers and ferns, that it was about public health.

I could feel the steel caucus and the utility people, their allies on the Hill, and everybody else gnawing at our heels. I said, "It's time to remind everybody what this is really all about." So I didn't try to spin doctor it.

The one thing that really bothered me was the leak of that chromosomal study, because I knew that it had not been peer reviewed, and it had to be. The study was leaked from the White House, not from us.

Although we never were in control of the way the story developed, I was all for getting it out. I think it was either Chris or I who said "ticking time bomb," and the phrase got picked up. Time published that wonderful cover that looked like a split photograph, with the upper part appearing normal and the bottom part a skull, the message being that what is lurking beneath the surface here, that we don't know about, would be very harmful.

Superfund and Toxic Substances

Q: So do you think Superfund legislation in general, and the Love Canal incident in particular, were net gains or net losses for EPA?

MR. COSTLE: I think it did a lot to force us all -- the Agency, the environmental community, business and industry -- to mature in our perspective of what many environmental problems are all about. There was a legacy out there. It is one thing to deal with gross pollution you can see, where rivers catch on fire, or there's a heavy plume from a smokestack. Everybody can visually understand that. What is much harder to understand is the ubiquitous presence of toxins in the environment, where you don't know what the long-term health effects or the mechanisms are. The ordinary, reasonable man using common sense would say our job is to reduce risk by reducing exposure and by making sure that we are not just simply creating new problems that we will have to deal with later.

I'll give you a graphic illustration. Steve Gage and his R&D people wanted to build an activated carbon filtration plant at our Cincinnati laboratory, which was EPA's major drinking water lab. They needed $40 million. That was a lot of money in those days. When I asked why, they said, "We've been sampling drinking water, using newer technologies of gas chromatography and mass spectrometry. We can detect things now that we couldn't a while back. We have found over 700 synthetic organic chemicals in finished drinking water, of which eleven are either known or suspected carcinogens, based on animal studies. Well over 20 or 30 percent of these chemicals are relatively new inventions." That is, they were substances that hadn't existed 20 years earlier but were just showing up now in sediments.

I said, "Are you telling me that water is not safe to drink?" They said, "No. We don't know that. It will take several thousand mice, a team of technicians, and several years to analyze, chemical-by-chemical, and even then we don't have the methodology to determine what effects two or more of these chemicals interacting might produce, as opposed to each acting individually. By the same token, we are not telling you that the water is safe to drink. What we're telling you is that we don't know, and there is no scientific silver bullet that is going to give us the answer. So we want to build this laboratory to see how effectively it can strip these chemicals out of this water."

About that time, we had been having a real knock-down, drag-out fight with the American Waterworks Association, which was opposing the testing of drinking water. Water suppliers were afraid that, if they found high chemical levels, they would then be required to do something about it. Gage said, "We want to set up an activated carbon unit, treat the water, cost it out, and figure out how efficacious and costly the technology is, whether it is perhaps an affordable insurance policy against our ignorance on the larger question of whether this water is safe to drink." I immediately approved the project, even though it was a bit of a reach in the budget that year. The Reagan people canceled it, but I think EPA eventually went ahead with the testing.

This experience encapsulated for me the essence of the issues that this new generation of pollution control was going to encompass. Substances show up, not just in one place, but across many media -- air, water, land -- often simultaneously. The public health concern then becomes the total body burden: what exposure are you getting?

The experience also illustrated the dilemma with the science of risk assessment, which is both factually- and assumption-driven. It is driven as much by the assumptions that you incorporate in the risk models as it is by whatever numbers you can plug into those models. Either way, you are frequently going to be arguing about things over which reasonable men could disagree.

At the same time, we are saddled with a legal system which basically presumes that the framework for dealing with a problem is that there must be a number above which you are all right and below which you are in trouble. Since the laws are written largely by lawyers, the authors want a bright line for ease of enforcement and implementation. EPA is supposed to set a number that will both protect and reassure the public.

It is clear from examples like that of the drinking water that the odds are, the minute you pick a number, it is arguably wrong. I saw this phenomenon again in setting air standards. When we convened an outside panel of scientists to advise us on air standards, we had studies that were clustered all over the lot. Even if we had done another twenty studies, we would probably still be in the same position. We had finally drawn a band, with upper and lower limits somewhere within where we thought the standard ought to be set. We then had this independent panel of scientists look at the characterization studies and agree on the upper and lower bands. Then we set the standards within those bands.

This reflects the nature of dealing with what I characterized then as the chemical revolution, dealing with uncertainties about which people are going to disagree, and where anybody will be able to quarrel with whatever number we pick. Nonetheless, we have to reduce risk somehow by reducing exposure, so we have to start somewhere.

So what is the nature of our job? It is to use common sense to reduce risk by reducing exposure, to take a harder look at new substances before we introduce them into commerce. But let's not kid ourselves that we are smart enough to know how to draw the bright line, or that there is a single scientifically sound way to do that.

In some ways it was an intellectual coming-of-age for the Agency to find itself suddenly dealing with a different universe of problems. It was never intended that we would drift away from the original environmental quality-of-life issue, but we did become preoccupied with health concerns. I don't think we are going to get a good resolution of this quantitative risk assessment debate until we face up to the reality that what we are doing is reducing risk by reducing exposure. It is legitimate to look at the cost-effectiveness of the ways in which to do that. That requires the politics to follow the facts. It is when you try to make the facts stand for more than they do that you get into long-term problems of credibility.

EPA and the Public

Q: You seem to have a lot of faith in the idea that the common person, given the information, can make good choices.

MR. COSTLE: I think they can make common-sense, practical choices. That is always what it comes down to, anyway. I think that, if you do to people what they did to the people at Love Canal, with the leak of those unreviewed chromosome studies, you have put yourself in an impossible position. You have to get in early, to have the affected people participate in the process every step of the way. That is beginning to happen now with clean-ups at the old defense facilities at DOE, and it's working.

Q: You talk about common sense and also about the ambiguity of science. Yet, there is this deep sort of trust of science and technology in the American psyche. How do you grapple with that, or how did you, as a regulator? Or were you even aware of that?

MR. COSTLE: Every time we had to recalibrate a standard or set a new one, we faced this. You can't be in that business and not be aware of the uncertainties and ambiguities in the science. People tend to think science is hard and numerical and precise. It's not, particularly in the environmental area. But there is one way, and only one way, to deal with that, and that is just to be absolutely open and honest about the gray areas. Anyway you cut it, we're making judgments, social policy judgment calls, and we have to be willing to tolerate a certain level of intervention in the operation of a free market economy. We're forcing the internalization of externalities, and this must become a part of our economic decision-making. We're going to have to set some boundaries that will by nature be arbitrary. We can reduce the edge of the arbitrariness with research and with refinement of the science as we go along, but we are never going to get the kind of precision that we'd like. So we have either got to change our system for making these decisions, or we have got to live with this ambiguity. The cumulative effect of so many of these problems is gradual, and you can very easily reach a point of no return. That's what makes these problems so poignant.

I remember a group of scientists from Russia, China and the United States telling me, about 1978 or '79, that by the time they could definitively document global warming, it would be too late to implement preventive measures, so complicated was the job of tracking chemistry in the atmosphere and sorting out the impacts of man-induced climate change from normal weather variations over multi-year time periods. The only way I know to deal with such problems is to be straight up about what we know and what we don't.

Risk Assessment

Q: Does risk assessment help?

MR. COSTLE: I think it can help you organize what you know. And it can underline what you don't know, which may be more important in the ultimate judgment call than what you do. But it is just a tool to help organize our knowledge.

Q: Is that why you got into risk assessment?

MR. COSTLE: There was enormous pressure to come up with more rational defenses of the standards we were setting, and risk assessment was an emerging and promising tool. But I remember cautioning EPA scientists at the time not to put all our eggs in one basket, such as cancer risks. People would not understand risk assessment jargon, or numbers. That's why, for example, when I had to make a decision about diesel emissions, I refused to base that standard solely on cancer risks. I also looked at other reasons to worry about these emissions, such as effects on asthma. And across the board I urged the Agency to look at impacts on areas like gene structure, chromosomes, and reproductivity, in addition to cancer.

Q: Why was cancer such a huge issue?

MR. COSTLE: It was so immediately scary. Cancer statistics seemed to be going up. There had been press exposes about the rapid rise in cancer, from different causes, in different age groups. You had DES (Diethylstilbesterol) and thalidomide stories, reports of problems that are at first latent and only show up much later. That kind of publicity was guaranteed to panic people. Even if only some few panicked, however, it clearly concerned any reasonable person that maybe we -- society -- didn't know what we were doing. In a public health sense, if you wait until the bodies stack up, you have lost the game. In that way, environmental protection is more analogous to public health medicine than to curative medicine.