About Geoengineering

Geoengineering encompasses a broad range of activities, including those that intentionally attempt to cool the Earth or remove certain gases from the atmosphere. Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere are often referred to as greenhouse gases, which include carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. For example, geoengineering includes the removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere (also called Carbon Dioxide Removal – CDR) through methods such as direct air capture and storage, ocean iron fertilization, or ocean alkalinity enhancement.

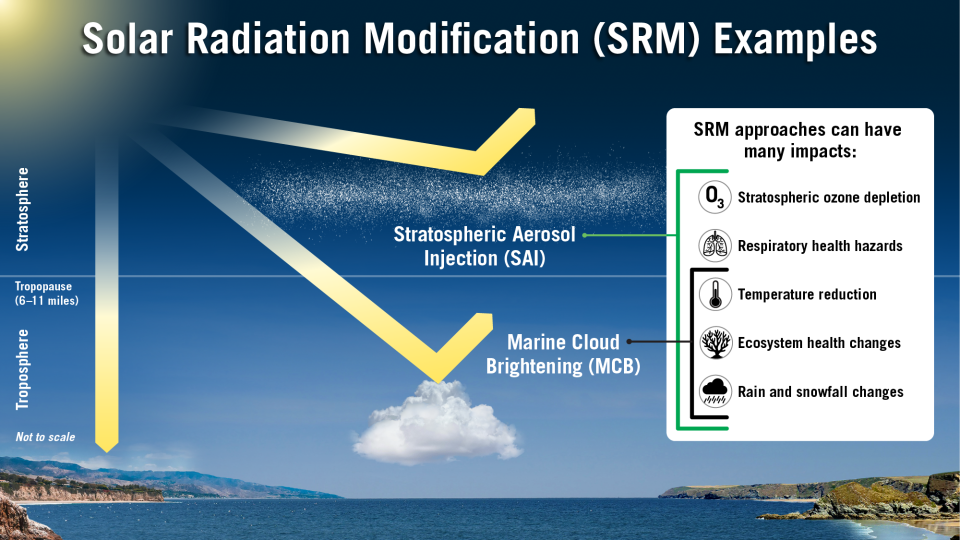

A subset of geoengineering activities intends to cool the Earth by intentionally modifying the amount of sunlight reaching Earth’s surface. These activities are referred to as Solar Geoengineering or Solar Radiation Modification (SRM). Most proposed solar radiation modification techniques involve adding material to the atmosphere to increase the amount of incoming sunlight reflected back to space. While some of these approaches are currently being studied, not enough information exists to fully understand the viability, risks, and benefits of each approach.

Types of solar geoengineering techniques include:

Stratospheric Aerosol Injection (SAI) – adding small reflective particles to the upper atmosphere (stratosphere) to reflect incoming sunlight. Sulfur dioxide (SO2), one of the types of chemicals considered for SAI, can chemically react in the stratosphere to form reflective sulfate aerosols.

Marine Cloud Brightening (MCB) – adding particles, such as sea spray, to the lower atmosphere (near the surface) to increase the reflectivity of clouds over the ocean.

Other techniques, such as Cirrus Cloud Thinning (CCT) or space-based methods have been far less researched due to uncertainty in the processes, high potential costs, and more limited feasibility.

Potential Impacts

The purpose of solar geoengineering is to cool the Earth by reflecting more sunlight back to space. Depending on the approach used, there could be additional unintended health and environmental consequences that require careful evaluation. Current understanding of risks and benefits is limited by uncertainties in the observations and modeling tools used to examine solar geoengineering impacts. There isn’t enough information available to fully understand the unintended consequences of solar geoengineering.

Potential health and environmental impacts of solar geoengineering include:

Ozone – adding particles to the stratosphere could lead to stratospheric ozone layer depletion; however, lower temperatures from reduced sunlight may also reduce ozone at ground-level and its negative health impacts.

Ecosystem health and crop yields – adding sulfur to the atmosphere increases the risk of acid rain, deposition of sulfur to the surface, and worsened soil acidity, which could impact food production. Decreased sunlight (i.e., energy) reaching the surface could also impact ecosystem and agricultural productivity.

Rain and snowfall patterns – adding particles to the stratosphere can alter hydrological cycles, leading to changes in the amount of rainfall and drought in specific regions.

Respiratory health – some particles in the stratosphere eventually come down to Earth’s surface where they can contribute to adverse health impacts, including making it difficult to breathe.