Climate Change Connections: Alaska (Dogsledding and The Iditarod)

Climate change is impacting all regions and sectors of the United States. The State and Regional Climate Change Connections resource highlights climate change connections to culturally, ecologically, or economically important features of each state and territory. The content on this page provides an illustrative example. As climate change will affect each state and territory in diverse ways, this resource only describes a small portion of these risks. For more comprehensive information about regional climate impacts, please visit the Fifth National Climate Assessment and Climate Change Impacts by Sector.

On this page:

Introduction: Dogsledding Is an Essential Part of Alaskan Culture

Dogsledding (also known as mushing) is a form of transportation across snow and ice that has been used for thousands of years in the Arctic region. Indigenous Peoples in these regions bred dogs, such as the Alaskan malamute and the Siberian husky, that are well suited to carrying people and heavy loads long distances across snow and ice.

Dogsledding became even more popular in Alaska during the gold rush, when prospectors relied on dogsleds to access gold in Alaska’s wilderness. Dogsledding was commonly used for travel, mail delivery, and gold transportation during winter months in the early 20th century. By the mid-20th century, snowmobiles (known locally as “snow machines”) became a more dominant form of transportation in rural areas, though dogsleds remained important.1

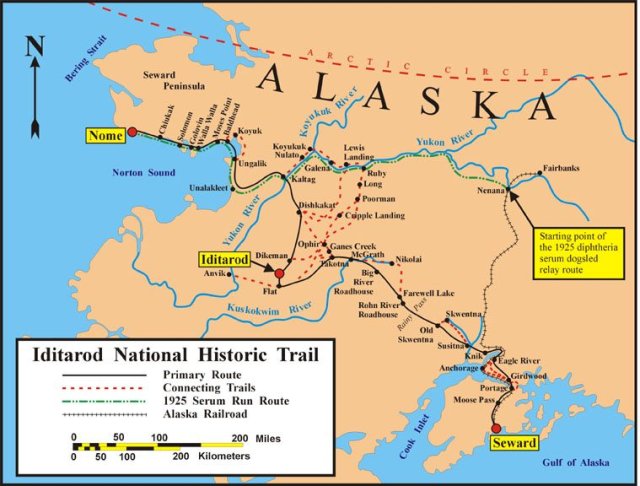

Alaskan dogsledding achieved a new level of recognition in 1925, when a relay of dogsled teams saved the town of Nome, Alaska, from an outbreak of diphtheria. The sled dogs transported life-saving serum 674 miles across a portion of what is now the Iditarod Trail in sub-zero temperatures in a record 127.5 hours (about 5 days).2 In 1973, as part of the Alaska Centennial celebration, a team conceived the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race, an annual dogsledding competition, to celebrate sled dog culture and the 1925 serum run. The route stretches roughly 1,000 miles from Anchorage to Nome, following historic Native routes. 3 As the premier event in dogsled racing, the Iditarod travels through more than 25 communities, depending on the route, and crosses the Tribal lands of the Athabascan, Yup’ik and Cup’ik, and Iñupiaq people .4

Since the Iditarod’s very first year, Alaska Native mushers have participated in the race using their skills and Indigenous Knowledge of the region to overcome obstacles along the route.4 Dogsledding was, and remains in some areas, an essential component of Alaska Native life and culture. Dogsledding can be an activity around which community members—both young and old—come together. For example, a youth and sled dog care mushing program in Huslia, a relatively new stop on the Iditarod route, has had a considerable positive impact on the community.5 Dogsledding helps build confidence and a sense of purpose in the younger generation, while also creating common ground between younger and older generations and strengthening Indigenous Knowledge . The Iditarod Trail was designated a national historic trail in 1978.6 Other well-known races include the Yukon Quest that runs from Fairbanks, Alaska, to Whitehorse, Yukon; the Kuskokwim 300 that traverses the Yukon Delta; and the Bogus Creek 150, which is a round-trip race from Bethel to Bogus Creek in southwestern Alaska.

Climate Impacts: Alaska Faces Major Warming

Concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases are increasing in the Earth’s atmosphere, and average temperatures at the Earth’s surface are increasing and are expected to continue rising. Some parts of the world, such as the Arctic, are warming faster than others. Alaska is experiencing a rate of warming that is two to three times the global average. 7 This warming is melting glaciers and sea ice. Warming temperatures are also affecting permafrost, a layer beneath the soil surface that stays frozen year-round in northern climates and underlies roughly 80 percent of Alaskan territory.8,9 As permafrost thaws, it can turn into a mud slurry that cannot support the weight of the soil and vegetation above, often damaging roads, buildings, and pipes, which can harm people and infrastructure.8

Warming can affect Alaskan ecosystems, communities, and traditions like the Iditarod. The warming temperatures and lack of snow have prompted shifts in the Iditarod Trail location in multiple years.10 While the ceremonial start of the Iditarod remains in Anchorage, low amounts of snow coupled with urban sprawl necessitated permanently moving its timed, competitive starting point from Wasilla further north to Willow in 2008.11 In 2003, 2015, and 2017, the race’s competitive starting point moved further north to Fairbanks due to a lack of snow.12,13 The changing environmental conditions mushers face during the Iditarod and other dogsledding races are just one of the many examples of climate-related impacts affecting Alaska’s landscape and threatening Tribes and communities.7

Climate change is causing the breakup of river ice, reduced sea ice cover, and glacial retreat in Alaska.14–16 Snow and ice enable travel by dogsled or snowmobile in rural Alaska, which has limited infrastructure like roads and bridges. In these places, winter trails are the main method of transportation between villages to visit family, purchase goods, and seek medical care.17 Earlier snowmelt, less stable sea ice, and earlier breakup of river ice reduce the seasonal length for winter trail travel, increase wear and tear on snowmobiles and sleds, and make travel over frozen water bodies more dangerous and unpredictable.7,17 Changing conditions can threaten Indigenous sled dog culture and traditions. Community programs, like the Frank Attla Youth and Dog Sled Care-Mushing Program, seek to enhance connections for Native youth and dogsledding, preserve cultural traditions, and promote youth wellness.5

Taking Action: Preserving Tradition in a Warming World

Addressing climate change requires reducing greenhouse gas emissions while preparing for and protecting against current and future climate impacts. Communities, public officials, and individuals in every part of the United States can continue to explore and implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures. Alaska faces accelerating warming temperatures, thawing permafrost, and changing snow patterns that will further disrupt many ways of life, including traditions like dogsledding. Climate change means the future of the Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race will likely look different. Organizers have explored adjustments, including:

- Changing the route. Warming temperatures and thawing permafrost may require continued adjustment of the schedule and route. The route has been adjusted multiple times in the past.

To learn more about climate change impacts in Alaska, see Chapter 29 of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Related Resources

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Permafrost

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Arctic Sea Ice

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Community Connection: Ice Breakup in Three Alaskan Rivers

- The Arctic, Alaska, and Climate Change (EPA)

- Adapt Alaska (U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit)

- Community Resilience Programs (State of Alaska)

- Alaska State Climate Summary 2022 (NOAA)

- Alaska and a Changing Climate (USDA Climate Hubs)

References

1 Andersen, D. B. (1992). The use of dog teams and the use of subsistence-caught fish for feeding sled dogs in the Yukon River Drainage, Alaska (Technical Paper No. 210). Alaska Department of Fish and Game. https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/download/Technical%20Papers/tp210.pdf

2 Alaska State Archives. (2019). Serum run of 1925. Alaska State Libraries, Archives & Museums. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://archives.alaska.gov/education/serum.html

3 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (2012). The Iditarod sled dog race in Alaska. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.fws.gov/media/iditarod-sled-dog-race-alaska

4 Westrich, J. (2022). Legacy of the land. Iditarod EDU. Retrieved February 22, 2024, from https://iditarod.com/edu/legacy-of-the-land/

5 Newman, J., Rivkin, I., Brooks, C., Turco, K., Bifelt, J., Ekada, L., & Philip, J. (2022). Indigenous knowledge: Revitalizing everlasting relationships between Alaska Natives and sled dogs to promote holistic wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20010244

6 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management. (n.d.). Iditarod National Historic Trail. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.blm.gov/programs/national-conservation-lands/national-scenic-and-historic-trails/iditarod

7 Huntington, H. P., Strawhacker, C., Falke, J., Ward, E. M., Behnken, L., Curry, T. N., Herrmann, A. C., Itchuaqiyaq, C. U., Littell, J. S., Logerwell, E. A., Meeker, D., Overbeck, J. R., Peter, D. L., Pincus, R., Quintyne, A. A., Trainor, S. F., & Yoder, S. A. (2023). Ch. 29. Alaska. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH29

8 EPA. (2021). Climate change indicators: Permafrost. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-permafrost

9 Osterkamp, T. E., & Jorgenson, M. T. (2009). Permafrost conditions and processes. In R. Young & L. Norby, Geological Monitoring. Geological Society of America. https://doi.org/10.1130/2009.monitoring(09)

10 Greenhalgh, E. (2017, March 13). Low snow drives Iditarod north for third time. NOAA Climate.gov. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/features/low-snow-drives-iditarod-north-third-time

11 Rosen, Y. (2008, February 28). Climate change and urban sprawl alter Iditarod race. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/environment-alaska-iditarod-dc/climate-change-and-urban-sprawl-alter-iditarod-race-idUSN2847616320080228/

12 Iditarod Trail Committee. (2017, February 10). Restart moved to Fairbanks on March 6th. Iditarod Insider. Retrieved February 22, 2024 from https://iditarod.com/restart-moved-to-fairbanks/

13 Kennedy, C. (2015, March 10). Lack of snow drives Iditarod start 250 miles north. NOAA Climate.gov. Retrieved January 23, 2024, from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/featured-images/lack-snow-drives-iditarod-start-250-miles-north

14 EPA. (2022). Community connection: Ice breakup in three Alaskan rivers. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/alaskan-rivers

15 EPA. (2023). Climate change indicators: Arctic sea ice. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-arctic-sea-ice

16 EPA. (2016). Climate change indicators: Glaciers. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-glaciers

17 Beck, A., Carpenter, M., Chapman, J., Keller, J., & Woolery, A. (2022). Northwest Alaska Transportation Plan: Key findings. https://dot.alaska.gov/stwdplng/areaplans/area_regional/assets/nw/Northwest-Alaska-Transportation-Plan-Update-2022.pdf