Climate Change Connections: Puerto Rico (Coquí Frog)

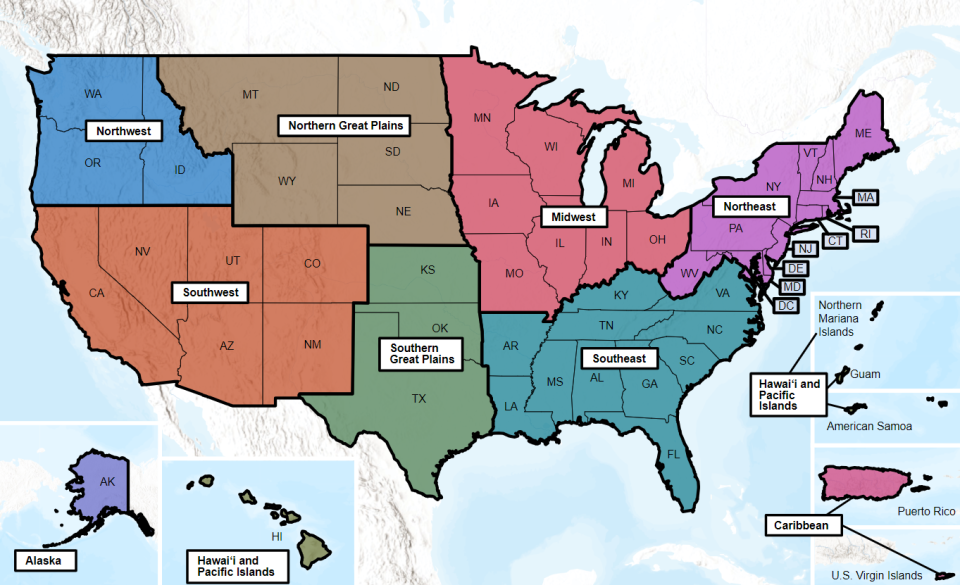

Climate change is impacting all regions and sectors of the United States. The State and Regional Climate Change Connections resource highlights climate change connections to culturally, ecologically, or economically important features of each state and territory. The content on this page provides an illustrative example. As climate change will affect each state and territory in diverse ways, this resource only describes a small portion of these risks. For more comprehensive information about regional climate impacts, please visit the Fifth National Climate Assessment and Climate Change Impacts by Sector.

On this page:

Introduction: The Coquí Frog—Cultural and Ecological Significance

Puerto Rico, which includes the smaller islands of Vieques and Culebra, is a U.S. territory located in the northeastern Caribbean Sea, approximately 1,000 miles southeast of Florida. It has a warm tropical climate year-round, moderated by mountainous and hilly terrain that creates cooler areas at higher elevations.1

Since long before the islands of Puerto Rico were first inhabited by people, nightfall in Puerto Rico has been punctuated by the distinctive call of the coquí. The common name “coquí” refers to at least 16 species of tiny native frogs of the genus Eleutherodactylus found in Puerto Rico. The name comes from the male frog’s loud mating call, which sounds like “ko-kee.”2 The common coquí (Eleutherodactylus coqui) is adaptable to a variety of habitats, from forests and mountains to urban areas, and has even become invasive in other parts of the world, such as Hawai‘i.2 While the common coqui is abundant, some of the 16 coquí species in Puerto Rico are classified as critically endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.3

The coquí has a deep significance to the people and culture of Puerto Rico. Dating back thousands of years, the coquí symbol commonly appears in Indigenous Taíno art, pictographs, and pottery.4 According to Taíno beliefs, the coquí frog was created by a goddess to help call for “Coquí,” her lost love.5 Today, the coquí remains a symbol of cultural pride for the 3 million U.S. citizens, predominantly Hispanic or Latino and Spanish-speaking, who call Puerto Rico home. A phrase that epitomizes the deep ties between the people of Puerto Rico and the coquí is “Soy de aquí, como el coquí”—“I am from here, like the coquí.”5 Climate change is expected to reduce and fragment prime habitat, which can impact species of coquí that depend on montane cloud forest and are sensitive to temperature and vulnerable to dryness.

Climate Impacts: Changes in Temperature and Rainfall Could Threaten Vulnerable Coquí Populations

Amphibians depend on their environment to maintain their temperature and moisture, which makes them particularly vulnerable to climate change.6,7 Climate stressors such as heavy rainfall, drought, more intense tropical cyclones, and warming temperatures are impacting ecosystems across the Caribbean.8 Some populations of coquí have already declined due to habitat destruction from the conversion of native habitat to agricultural and urban landscapes. Exposure to fungal disease has also impacted some frogs.9 Climate change is expected to put increasing stress on the frogs and their ecosystems.10

In Puerto Rico, the mountainous topography contributes to variable temperatures across the island. Across elevations, temperatures do not drop as much at night, which is when the coquí are most active. Since 1950, temperatures in Puerto Rico have risen approximately 2°F, with warmer daily minimum temperatures occurring at lower elevations in particular, and are projected to continue to increase across the Caribbean region.8,11 One study found that after more than two decades of warming forest temperatures, male coquí had higher pitched and shorter calls as well as smaller body sizes.12 As temperatures continue to rise due to climate change, the sounds and appearances of coquí are expected to change, which could potentially impact mating success.12,13

While average annual rainfall has not changed significantly over the past century, extreme rainfall events and drought intensity are increasing.8 Despite more large, concentrated bursts of rainfall, scientists expect Puerto Rico to receive less precipitation as global temperatures rise, leading to longer-lasting periods of drought between storms. Climate projections predict a decrease in annual rainfall, concentrated during a wetter rainy season, and an increase in drier conditions during other times of the year in Puerto Rico.11 Historically, dry conditions have been detrimental for coquí populations. A period of low rainfall between 1984 and 1989 was associated with a 60 percent decrease in the population density of the common coquí.13 Coquí may also be susceptible to harmful fungi during extended periods of drought.14

Intense precipitation may be associated with reduced calling activity in some species while the frogs take shelter from the rain.13 Tropical storms, which are also projected to increase in intensity,8,11 can affect coquí populations by changing their habitats’ temperature and structure.6,15 Based on the sensitivity of coquí to temperature and rainfall, researchers predict that more droughts and heavy rainfall events associated with climate change could affect the coquí’s reproductive capacity and survival.10,13 For species that have already declined in population, future climate change could increase their risk of extinction.9

Taking Action: Conservation in a Changing Climate

Addressing climate change requires reducing greenhouse gas emissions while preparing for and protecting against current and future climate impacts. Communities, public officials, and individuals in every part of the United States can continue to explore and implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures. In Puerto Rico, public agencies, organizations, and scientists are taking steps to protect habitat and research climate impacts on frogs to support the species in a changing climate, including:

- Expanding protected areas and relocation. Researchers and resource managers, such as those at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, are gathering information to help prevent at-risk species from becoming threatened or endangered.16 Expanding terrestrial protected areas to include buffer zones and connectivity may provide coquí with room to move into climate refugia, spaces where populations can withstand environmental changes.17,18 For critically endangered species, scientists are considering captive breeding and relocation programs to increase the likelihood of their survival.9,17

To learn more about climate change impacts in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Caribbean region, see Chapter 23 of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Related Resources

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Tropical Cyclone Activity

- Puerto Rico State of Climate 2014–2021 (Puerto Rico Climate Change Council)

References

1 Caribbean-Florida Water Science Center. (2016). Climate of Puerto Rico. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved January 24, 2024, from https://www.usgs.gov/centers/cfwsc/science/climate-puerto-rico

2 U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Common coqui. https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/elyunque/learning/nature-science/?cid=fsbdev3_043003

3 U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Richmond’s coqui. https://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/elyunque/learning/nature-science/?cid=fsbdev3_043020

4 Taíno Museum. (n.d.). Museum logo: Coqui frog. Retrieved November 30, 2023, from https://tainomuseum.org/logo/

5 Westrick, S. E., Laslo, M., & Fischer, E. K. (2022). The big potential of the small frog Eleutherodactylus coqui. eLife, 11, e73401. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.73401

6 Burrowes, P. A., Hernández-Figueroa, Á. D., Acevedo, G. D., Alemán-Ríos, J., & Longo, A. V. (2021). Can artificial retreat sites help frogs recover after severe habitat devastation? Insights on the use of “coqui houses” after Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation, 15(1), 57–70. https://amphibian-reptile-conservation.org/pdfs/Volume/Vol_15_no_1/ARC_15_1_%5BGeneral_Section%5D_57-70_e274.pdf

7 Hawley Matlaga, T. J., Burrowes, P. A., Hernández-Pacheco, R., Pena, J., Sutherland, C., & Wood, T. E. (2021). Warming increases activity in the common tropical frog Eleutherodactylus coqui. Climate Change Ecology, 2, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecochg.2021.100041

8 Méndez-Lazaro, P. A., Chardón-Maldonado, P., Carrubba, L., Álvarez-Berríos, N., Barreto, M., Bowden, J. H., Crespo-Acevedo, W. I., Diaz, E. L., Gardner, L. S., Gonzalez, G., Guannel, G., Guido, Z., Harmsen, E. W., Leinberger, A. J., McGinley, K., Méndez-Lazaro, P. A., Ortiz, A. P., Pulwarty, R. S., Ragster, L. E., … Vila-Biaggi, I. M. (2023). Ch. 23. US Caribbean. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH23

9 Barker, B. S., & Ríos-Franceschi, A. (2014). Population Declines of Mountain Coqui (Eleutherodactylus portoricensis) in the Cordillera Central of Puerto Rico. Herpetological Conservation and Biology, 9(3), 578–589. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4326090/

10 Delgado-Suazo, P., & Burrowes, P. A. (2022). Response to thermal and hydric regimes point to differential inter- and intraspecific vulnerability of tropical amphibians to climate warming. Journal of Thermal Biology, 103, 103148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2021.103148

11 Puerto Rico Climate Change Council (PRCCC). (2022). Puerto Rico’s state of the climate 2014-2021: Assessing Puerto Rico’s social-ecological vulnerabilities in a changing climate. Puerto Rico Coastal Zone Management Program, Department of Natural and Environmental Resources, NOAA Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management. https://www.pr-ccc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/PR_StateOfTheClimate_2014-2021_PRCCC-09-2022-1.pdf

12 Narins, P. M., & Meenderink, S. W. F. (2014). Climate change and frog calls: long-term correlations along a tropical altitudinal gradient. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281(1783), 20140401. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.0401

13 Ospina, O. E., Villanueva-Rivera, L. J., Corrada-Bravo, C. J., & Aide, T. M. (2013). Variable response of anuran calling activity to daily precipitation and temperature: Implications for climate change. Ecosphere, 4(4), art47. https://doi.org/10.1890/ES12-00258.1

14 Burrowes, P. A., Joglar, R. L., & Green, D. E. (2004). Potential causes for amphibian declines in Puerto Rico. Herpetologica, 60(2), 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1655/03-50

15 Collazo, J. A., Terando, A. J., Engman, A. C., Fackler, P. F., & Kwak, T. J. (2019). Toward a resilience-based conservation strategy for wetlands in Puerto Rico: Meeting challenges posed by environmental change. Wetlands, 39(6), 1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13157-018-1080-z

16 Climate Adaptation Science Centers. (2023). Eleutherodactylus coquí - A chronicle of conservation collaboration. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved August 6, 2024, from https://www.usgs.gov/programs/climate-adaptation-science-centers/news/eleutherodactylus-coqui-a-chronicle-conservation

17 Campos-Cerqueira, M., Terando, A. J., Murray, B. A., Collazo, J. A., & Aide, T. M. (2021). Climate change is creating a mismatch between protected areas and suitable habitats for frogs and birds in Puerto Rico. Biodiversity and Conservation, 30(12), 3509–3528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-021-02258-9

18 Rivera-Burgos, A. C., Collazo, J. A., Terando, A. J., & Pacifici, K. (2021). Linking demographic rates to local environmental conditions: Empirical data to support climate adaptation strategies for Eleutherodactylus frogs. Global Ecology and Conservation, 28, e01624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01624