Climate Change Connections: Montana (Glacier National Park)

Climate change is impacting all regions and sectors of the United States. The State and Regional Climate Change Connections resource highlights climate change connections to culturally, ecologically, or economically important features of each state and territory. The content on this page provides an illustrative example. As climate change will affect each state and territory in diverse ways, this resource only describes a small portion of these risks. For more comprehensive information about regional climate impacts, please visit the Fifth National Climate Assessment and Climate Change Impacts by Sector.

On this page:

Introduction: Glacier National Park in Montana Hosts Spectacular Glaciers and Rich Biodiversity

In a state with many remarkable landscapes, Glacier National Park stands apart. Evidence of human presence in the Glacier National Park area stretches back more than 10,000 years.1 Native American Tribes, including the Blackfeet, Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Kootenai lived in the region and depended on the mountainous landscape for hunting, fishing, gathering plants, and conducting ceremonies.2 The eastern half of Glacier National Park is the ancestral home of the Blackfeet, who were forced to cede the land in 1895. The Park shares a border with the Blackfeet Reservation, which is home to nearly 8,600 members of the Blackfeet Nation.2 The region holds tremendous cultural and spiritual value for the Tribe, and they refer to it as the “Backbone of the World.”3

Glacier National Park became a National Park in 1910. Today, the park is one of the most-visited National Parks in the United States, attracting nearly 3 million visitors annually on average in recent years.4 Visitors come to enjoy biking, fishing, camping, sightseeing, and hiking among more than 700 miles of trails.5 Tourism contributes significantly to the Montana economy and supports thousands of jobs.6

The park boasts abundant plants and wildlife, impressive mountains, and turquoise lakes. Due to the park’s large size (over 1 million acres), it is one of the few areas in the contiguous United States where many large mammals, such as grizzly bears, elk, lynx, wolverines, mountain lions, and mountain goats, can thrive.7

Glaciers are the crown jewel of the park, and its namesake. A glacier is a mass of ice so big that it flows very slowly under its own weight.8 For thousands of years, glaciers in the park have cycled through periods of advance and retreat.9 During the last major glaciation, about 20,000 years ago, Glacier National Park was completely covered by glaciers so expansive that they constituted part of a regional ice sheet.10 As the ice sheet retreated, these glaciers shaped the valleys and steep cliffs that form the park’s dramatic landscape today.

The park’s glaciers provide critical benefits to the environment and to people.11 Glaciers are important water reservoirs, storing snow and ice during the winter and releasing ice melt into rivers and streams during the summer. Many aquatic species in Glacier National Park and the surrounding region depend on the addition of cold fresh water during the late summer months, when streamflow would otherwise be low.12 In many areas, glaciers provide communities with a reliable source of streamflow and drinking water, particularly during extended drought periods and late in the summer, when the seasonal snowpack has melted away.13

Climate Impacts: Glaciers Could Disappear from the Park by 2100

Glaciers are dynamic, meaning that they naturally vary in shape throughout the year. They also change in response to climate, temperature, and snowfall. A glacier will shrink or recede over time if more ice melts during the summer than the next winter’s snow can replenish over multiple seasons.14

There were an estimated 150 glaciers in the Glacier National Park area in 1910.10 By 2015, this number shrank to just 26. Between 1966 and 2015, the total surface area of glaciers in the park decreased by about 34 percent, with every glacier experiencing some amount of shrinking.15 With continued warming, scientists project the near-total loss of glaciers in the park by the end of the 21st century.16

Warming temperatures in Montana have contributed to the steep decline in glaciers in Glacier National Park over the last century. Average temperatures in Montana have increased by almost 2.5°F since the beginning of the 20th century, with Glacier National Park warming at nearly twice the global average.9,17 Scientists expect warming in the state to continue, and for more precipitation to fall as rain rather than snow.17 Less snowfall can make it more difficult for glaciers to grow in the winter and may not compensate for summer melting.

Diminishing Glaciers Have Major Implications for Ecosystems and Economy

The loss of glaciers in Glacier National Park will have impacts beyond the loss of the park’s namesake. Glacial melt provides an important water source during the summer, especially when rainfall is low. As summer droughts in Montana are expected to become more intense, a weakening or disappearing water source will affect many different sectors in the state.17 Glaciers in the park currently drain into rivers that are used for agriculture and hydroelectric power.12 The disappearance of the park’s glaciers could reduce power generation and increase competition for water for irrigating crops.12

Summer meltwater also provides a consistent source of colder water for streams. Coldwater fish species, such as trout, can die if stream temperatures get too warm or if parasites or diseases flourish in warmer waters.18,19,20 Warmer stream temperatures also foster habitat for invasive species that can compete with native species for food and resources. The loss of glaciers in the park could put increased stress on already-threatened native species, such as trout.21 These changes can also affect recreational fishing, as streams and lakes are often closed during periods of high temperatures, drought, or fish diseases to protect already-stressed fish populations.18,22

Warming temperatures and melting glaciers could affect tourism as well. With warming monthly temperatures, the season favorable to visitors could lengthen.23,24 However, surveys show that people would be less likely to visit the region if all the glaciers were lost.25

Taking Action: Education and Conservation in a Changing Climate

Addressing climate change requires reducing greenhouse gas emissions while preparing for and protecting against current and future climate impacts. Communities, public officials, and individuals in every part of the United States can continue to explore and implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures. The rapidly disappearing glaciers in Glacier National Park are visible examples of climate change impacts that offer an important education opportunity for visitors. Park officials and local stakeholders are collaborating on outreach and expanding conservation around the park to promote resiliency, including:

- Outreach and education. Glacier National Park participates in the National Park Service Climate Friendly Parks Program, which shares resources about climate-friendly practices with visitors.26 Planned improvements for Glacier National Park include enhancing conservation programs that target species vulnerable to climate change, including bison and whitebark pine.27 The Park also works to educate park visitors on climate-related issues affecting the park, and models sustainable practices that help mitigate climate impacts, including energy efficiency.28,29 Educating visitors about the park’s ecological importance and simultaneous vulnerability strengthens the case for conservation efforts.

- Conservation. Glacier National Park is large, but it also sits inside a larger intact ecosystem which covers more than 10 million acres, mostly publicly owned. This large protected area allows animals and plants to move in response to changing habitats and climates without being blocked by development or agriculture. The State of Montana, in collaboration with private conservation groups and the federal government, has continued to purchase land in the region to further buffer this important natural ecosystem and protect it from commercial development.

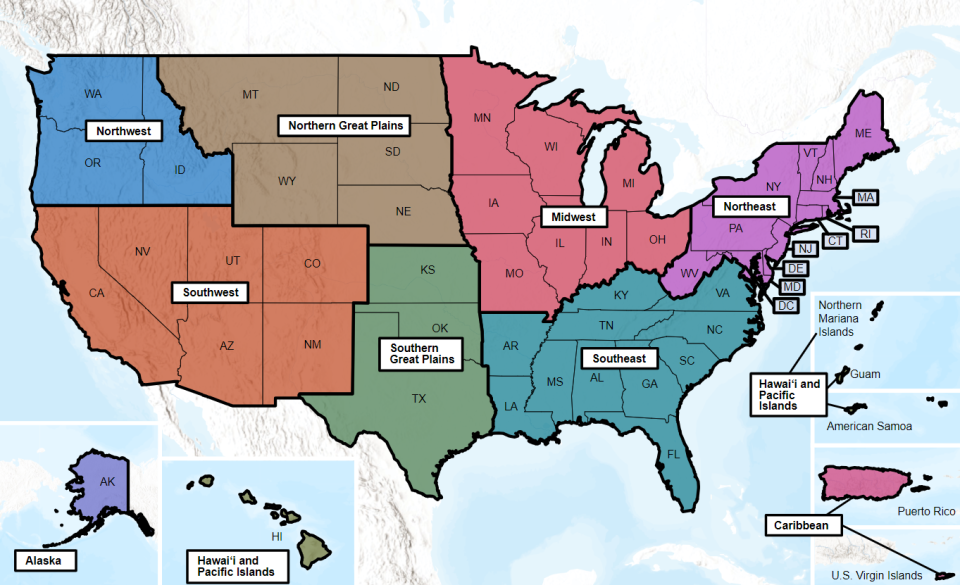

To learn more about climate change impacts in Montana and the Northern Great Plains region, see Chapter 25 of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Related Resources

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Glaciers in Glacier National Park

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Glaciers

- Climate Change in Glacier National Park (U.S. National Park Service)

- Montana Climate Office (University of Montana)

- Montana State Climate Summary 2022 (NOAA)

References

1 Blackfeet Nation. (n.d.). Our culture. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://blackfeetnation.com/our-culture/

2 National Park Service. (2020). American Indian Tribes. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/historyculture/tribes.htm

3 Craig, D. R., Yung, L., & Borrie, W. T. (2012). “Blackfeet belong to the mountains”: Hope, loss, and Blackfeet claims to Glacier National Park, Montana. Conservation and Society, 10(3), 232–242. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.101836

4 National Park Service. (2023). GNP announces 2022 visitation data. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/gnp-announces-2022-visitation-data.htm

5 National Park Service. (2022). Hiking the trails. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/planyourvisit/hikingthetrails.htm

6 National Park Service. (2023). Tourism to Glacier National Park contributes $548M to local economy. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/tourism-to-glacier-national-park-contributes-548m-to-local-economy.htm

7 National Park Service. (2023). Mammals. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/nature/mammals.htm

8 National Park Service. (2023). Overview of Glacier National Park’s glaciers. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/nature/glaciersoverview.htm

9 National Park Service. (2022). Climate change. Glacier National Park. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/nature/climate-change.htm

10 U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). Geology of Glacier National Park. Geology and Ecology of National Parks. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.usgs.gov/geology-and-ecology-of-national-parks/geology-glacier-national-park

11 EPA. (2024). Ecosystem services – EnviroAtlas. EnviroAtlas. Retrieved December 22, 2023, from https://www.epa.gov/enviroatlas/ecosystem-services-enviroatlas-1

12 Clark, A. M., Harper, J. T., & Fagre, D. B. (2015). Glacier-derived August runoff in northwest Montana. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 47(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1657/AAAR0014-033

13 EPA. (2023). Climate change indicators: Glaciers. Retrieved January 12, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-glaciers

14 Fagre, D. B., McKeon, L. A., Dick, K. A., & Fountain, A. G. (2017). Glacier margin time series (1966, 1998, 2005, 2015) of the named glaciers of Glacier National Park, MT, USA [Data set]. U.S. Geological Survey. https://doi.org/10.5066/F7P26WB1

15 EPA. (2021). A closer look: Glaciers in Glacier National Park. Retrieved June 28, 2023, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/closer-look-glaciers-glacier-national-park

16 Bosson, J.-B., Huss, M., & Osipova, E. (2019). Disappearing world heritage glaciers as a keystone of nature conservation in a changing climate. Earth’s Future, 7(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018EF001139

17 Frankson, R., Kunkel, K. E., Champion, S. M., Easterling, D. R., & Jencso, K. (2022). Montana state climate summary 2022 (NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 150-MT). NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. https://statesummaries.ncics.org/chapter/mt/

18 Knapp, C. N., Kluck, D. R., Guntenspergen, G., Ahlering, M. A., Aimone, N. M., Bamzai-Dodson, A., Basche, A., Byron, R. G., Conroy-Ben, O., Haggerty, M. N., Haigh, T. R., Johnson, C., Mayes Boustead, B., Mueller, N. D., Ott, J. P., Paige, G. B., Ryberg, K. R., Schuurman, G. W., & Tangen, S. G. (2023). Ch. 25. Northern Great Plains. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH25

19 Young, M. K., Isaak, D. J., Spaulding, S., Thomas, C. A., Barndt, S. A., Groce, M. C., Horan, D., & Nagel, D. E. (2018). Effects of climate change on cold-water fish in the Northern Rockies. In J. E. Halofsky & D. L. Peterson (Eds.), Climate change and Rocky Mountain ecosystems (pp. 37–58). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-56928-4_4

20 Christianson, K. R., & Johnson, B. M. (2020). Combined effects of early snowmelt and climate warming on mountain lake temperatures and fish energetics. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 52(1), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/15230430.2020.1741199

21 Bell, D. A., Kovach, R. P., Muhlfeld, C. C., Al-Chokhachy, R., Cline, T. J., Whited, D. C., Schmetterling, D. A., Lukacs, P. M., & Whiteley, A. R. (2021). Climate change and expanding invasive species drive widespread declines of native trout in the northern Rocky Mountains, USA. Science Advances, 7(52), eabj5471. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj5471

22 Cline, T. J., Muhlfeld, C. C., Kovach, R., Al-Chokhachy, R., Schmetterling, D., Whited, D., & Lynch, A. J. (2022). Socioeconomic resilience to climatic extremes in a freshwater fishery. Science Advances, 8(36), eabn1396. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn1396

23 Fisichelli, N. A., Schuurman, G. W., Monahan, W. B., & Ziesler, P. S. (2015). Protected area tourism in a changing climate: Will visitation at US National Parks warm up or overheat? PLOS ONE, 10(6), e0128226. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0128226

24 EPA. (2022). Climate change indicators: Seasonal temperature. Climate Change Indicators. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-seasonal-temperature

25 Scott, D., Jones, B., & Konopek, J. (2007). Implications of climate and environmental change for nature-based tourism in the Canadian Rocky Mountains: A case study of Waterton Lakes National Park. Tourism Management, 28(2), 570–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.04.020

26 National Park Service. (2024). Climate Friendly Parks Program. Climate Change. Retrieved December 15, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/climatechange/cfpprogram.htm

27 National Park Service. (2024). Glacier National Park announces $1.9M for ecosystem restoration and climate resilience projects. Glacier National Park. Retrieved July 9, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/glacier-national-park-announces-$1-9m-for-ecosystem-restoration-and-climate-resilience-projects.htm

28 Glacier National Park Conservancy. (2024). 2024 project funding needs: Protecting Glacier for future generations. https://glacier.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2024-Project-Funding-Needs-WEB.pdf

29 National Park Service. (2023). Glacier National Park: Sustainability. Retrieved July 9, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/glac/getinvolved/sustainability.htm