Climate Change Connections: Washington (Cascade Range)

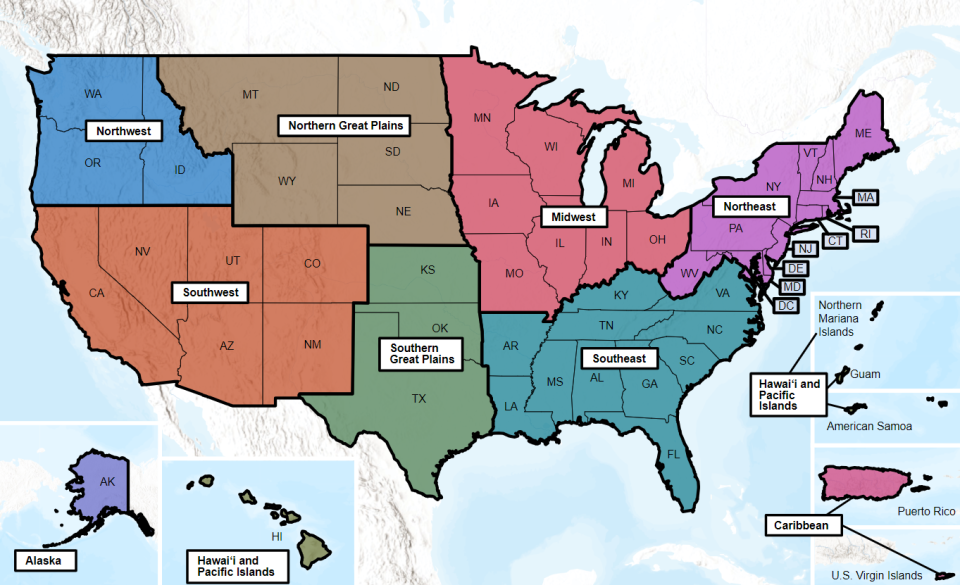

Climate change is impacting all regions and sectors of the United States. The State and Regional Climate Change Connections resource highlights climate change connections to culturally, ecologically, or economically important features of each state and territory. The content on this page provides an illustrative example. As climate change will affect each state and territory in diverse ways, this resource only describes a small portion of these risks. For more comprehensive information about regional climate impacts, please visit the Fifth National Climate Assessment and Climate Change Impacts by Sector.

On this page:

Introduction: The Cascades—Fundamental to Washington’s Economy and Ecology

Spanning across the Pacific Northwest, the Cascade Range, or simply the Cascades, features prominent peaks and diverse ecosystems. While the Cascades extend from northern California into Canada, for the state of Washington, they are a visible reminder of their importance to the state’s economy, ecology, and identity.

Snow is an integral part of the Cascades’ winter season. The Cascade Range contains four national parks (Crater Lake in Oregon, Lassen Volcanic in California, and Mount Rainier and North Cascades in Washington) where there are countless opportunities to enjoy skiing, snowmobiling, and snowshoeing.1 The prized mountaineering destination of Mt. Rainier boasts more than two million national park visitors every year.2 Visitor spending associated with the national parks in the Cascades contributes tens of millions of dollars in economic output for local economies each year.3

The Cascade Range, and specific mountains within it, also have deep spiritual and cultural importance to Tribes in the surrounding areas. For instance, several of the Coast Salish nations view Mount Baker as a sacred location, specifically for a sacred mental state called skalalitude that is fostered there.4 Further south, Mount Adams similarly holds spiritual significance for Indigenous peoples of the Yakama Nation and is partly managed by the Tribe.5

Climate Impacts: Warming Temperatures and Changing Snow Patterns Impact Glaciers and Ecosystems

Climate change is already affecting Washington’s natural systems. Since the beginning of the 20th century, average temperatures in the state have increased nearly 2°F.6 The changing temperature and precipitation patterns brought by climate change threaten to further alter the snow regime in the Cascades. For certain parts of the Cascade Range, scientists anticipate that the changing temperature and precipitation patterns will cut the snow season nearly in half by 2100.7 Skiing and snowmobiling seasons have already begun to start later and end earlier across the region.7

While the loss of snowpack could affect the economics of winter recreation, the environmental consequences last throughout the year. Most of Washington’s precipitation falls during the winter months.8 When snow accumulates, it serves as critical meltwater that feeds streams and rivers in the spring and summer. Since snowpack provides a natural source of water during drier summer months, changes in snowpack and shifts in the timing of snowmelt can make drought planning especially challenging. Since the 1950s, weather stations in the Cascades have seen significant reductions in the amount of snow available in early spring and the amount of winter precipitation falling as snow.9,10

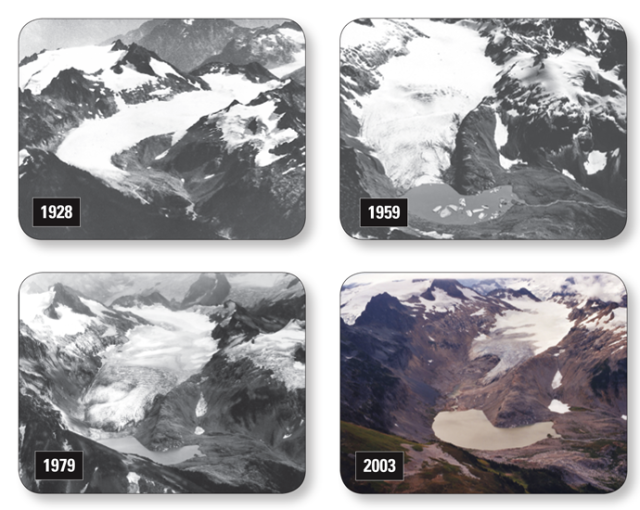

Washington also features the largest collection of glaciers in the contiguous United States, with more than 300 in North Cascades National Park alone.11 These large, moving, year-round masses of ice have existed for thousands of years and play an important role in the region’s water landscape. In some places, glacial melt represents more than 80 percent of a stream’s total discharge at certain times of year.12 Since the 1980s, glaciers throughout the Cascades have declined significantly due to warming temperatures.13–15

Belying their explosive volcanic origins, the Cascades are home to delicate alpine and subalpine ecosystems. In the North Cascades National Park ecosystem, there are eight distinctive life zones that support over a thousand different plant species, more than any other U.S. national park.16 The Cascades serve as habitats for distinctive plants like Pacific silver fir and animals such as the American pika, which thrive in the cold, high-elevation environment. Warming temperatures are expected to impact wildlife behavior, reproduction, and feeding patterns. Species have different sensitivities, and the distribution of impacts is dependent on a number of factors, including latitude and elevation.17 High daytime temperatures may cause animals like the pika to spend less time foraging and more time hiding in the shade.18,19 Studies in the broader Cascades have revealed that warming temperatures, especially when accompanied by low snowpack, can lead to sharp declines in certain mountain-dwelling animals, especially at lower elevations.20

Warming temperatures and changing precipitation patterns are also expected to change the dynamics of wildfires in the state. While wildfires are a natural part of the life cycle of western forests, climate change is expected to increase the intensity and season length of wildfires.7 Studies of wildfire records since the 1980s show that, across all 50 states, Washington had the second-highest increase in wildfire extent over a 35-year stretch.21 These ecological risks could also have economic impacts on industries that depend on healthy forests, such as the timber industry.7 Moreover, people exposed to wildfire smoke can experience numerous health impacts, including asthma and other respiratory complications.22

Taking Action: Preparing for Change

Addressing climate change requires reducing greenhouse gas emissions while preparing for and protecting against current and future climate impacts. Communities, public officials, and individuals in every part of the United States can continue to explore and implement climate adaptation and mitigation measures. In Washington state, many stakeholders are taking steps to respond to and prepare for climate change, including:

- Water management practices. By exploring strategies to address lower or intermittent water supplies, water managers can better prepare for annual variations. Water managers in Washington weigh the needs of all water uses: agricultural irrigation, in-home use, hydropower, and minimum streamflow for aquatic life. To increase drought awareness and allow for greater preparation, in 2020, Washington state legislature granted the authority to issue drought advisories ahead of drought emergencies. The advisories are informational and proactively encourage users to reduce their water consumption and increase drought readiness.23

- Sustainability-minded forest management. The Washington State Department of Natural Resources implements multiple approaches to manage the sustainability of forests on state lands.24 Collaborative efforts, such as the AirNow local air quality monitoring program, can help residents and emergency managers take safety measures to protect them from wildfire smoke.

- Collaboration with Indigenous experts. Indigenous peoples have lived in what is now Washington for millennia and have generations of experience managing the land. While climate change presents new and intensified environmental challenges, incorporating the knowledge from Indigenous communities can strengthen both the long-term resilience and social importance of vulnerable natural resources.

To learn more about climate change impacts in Washington and the Northwest region, see Chapter 27 of the Fifth National Climate Assessment.

Related Resources

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Snowpack

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Glaciers

- EPA Climate Change Indicators: Snowfall

- Washington State Climate Summary 2022 (NOAA)

- Washington Department of Health Climate Projections

References

1 North Cascades Institute National Forest Branch Funds. (n.d.). Mount Baker Ranger District, North Cascades National Park winter activity guide. https://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/fseprd899608.pdf

2 National Park Service. (2023). Frequently asked questions. Mount Rainier National Park. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/mora/faqs.htm

3 National Park Service. (2023). Visitor spending effects - Economic contributions of national park visitor spending. Social Science. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/subjects/socialscience/vse.htm

4 American Museum of Natural History. (n.d.). Coast Salish. Exhibitions. Retrieved February 15, 2024, from https://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/permanent/northwest-coast/coast-salish

5 U.S. Forest Service. (2023). Wilderness: Mt. Adams. Retrieved February 23, 2024, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/giffordpinchot/recarea/%3Frecid%3D79411

6 Frankson, R., Kunkel, K. E., Champion, S. M., Easterling, D. R., Stevens, L. E., Bumbaco, K., Bond, N. A., Casola, J., & Sweet, W. (2022). Washington state climate summary 2022 (NOAA Technical Report NESDIS 150-WA). NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. https://statesummaries.ncics.org/chapter/wa/

7 Chang, M., Erikson, L., Araújo, K., Asinas, E. N., Chisholm Hatfield, S., Crozier, L. G., Fleishman, E., Greene, C. S., Grossman, E. E., Luce, C., Paudel, J., Rajagopalan, K., Rasmussen, E., Raymond, C., Reyes, J. J., & Shandas, V. (2023). Ch. 27. Northwest. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH27

8 Raymond, C. L., Peterson, D. L., & Rochefort, R. M. (2014). Climate change vulnerability and adaptation in the North Cascades region, Washington (General Technical Report PNW-GTR-892). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. https://doi.org/10.2737/PNW-GTR-892

9 EPA. (2023). Climate change indicators: Snowpack. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-snowpack

10 EPA. (2023). Climate change indicators: Snowfall. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-snowfall

11 National Park Service. (2019). Glaciers/glacial features. North Cascades National Park. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/noca/learn/nature/glaciers.htm

12 Pelto, M. (2017). North Cascade Range, Washington USA. In Recent Climate Change Impacts on Mountain Glaciers (pp. 101–128). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119068150.ch8

13 North Cascade Glacier Mass Balance – North Cascade Glacier Climate Project. (n.d.). Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://glaciers.nichols.edu/north-cascade-glacier-mass-balance/

14 Pelto, M. (2016). Recent Climate Change Impacts on Mountain Glaciers. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119068150

15 National Park Service. (2021). Glacier Monitoring Program. North Cascades National Park. Retrieved July 11, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/noca/learn/nature/glacial-mass-balance1.htm

16 National Park Service. (2024). Plants [North Cascades National Park]. Retrieved July 11, 2024, from https://www.nps.gov/noca/learn/nature/plants.htm

17 Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. (2015). Chapter 5. Climate change vulnerability of species and habitats in Washington (Washington’s State Wildlife Action Plan: 2015 Update). Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. https://wdfw.wa.gov/sites/default/files/publications/01742/7_Chapter5.pdf

18 Smith, A. T., & Weston, M. L. (1990). Ochotona princeps. Mammalian Species, 352, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.2307/3504319

19 Millar, C. I., Westfall, R. D., & Delany, D. L. (2016). Thermal components of American pika habitat—How does a small lagomorph encounter climate? Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research, 48(2), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1657/AAAR0015-046

20 Northern Rocky Mountain Science Center. (2018). Alpine wildlife and snowpack dynamics in the North Cascades. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.usgs.gov/centers/norock/science/alpine-wildlife-and-snowpack-dynamics-north-cascades

21 EPA. (2024). Climate change indicators: Wildfires. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/climate-change-indicators-wildfires

22 West, J. J., Nolte, C. G., Bell, M. L., Fiore, A. M., Georgopoulos, P. G., Hess, J. J., Mickley, L. J., O’Neill, S. M., Pierce, J. R., Pinder, R. W., Pusede, S., Shindell, D. T., & Wilson, S. M. (2023). Chapter 14: Air Quality. In Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH14

23 Washington State Department of Ecology. (n.d.). Drought response. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://ecology.wa.gov/water-shorelines/water-supply/water-availability/statewide-conditions/drought-response

24 Washington State Department of Natural Resources. (n.d.). Forest resources. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.dnr.wa.gov/page/forest-resources-0