Water Quality for Healthy Corals (EPA Office of Water)

Quick Look

Collaboration Goal:

As a joint effort of the EPA Office of Water (OW) with the EPA Office of Research and Development (ORD), apply the Organon as an action and decision-making logic cycle to use in collaboration with jurisdictions (states, territories, and freely associated states) for addressing water quality issues for coral reefs.

Process:

EPA staff engaged in an intensive two-day meeting to develop a training flow for future work with coral reef jurisdictions to:

- Organize current information on priority water quality (WQ) parameters that negatively impact corals and whether current WQ standards criteria are protective/needed.

- Evaluate regulatory and non-regulatory pathways for protecting WQ for corals.

- Explore strategic design of WQ management interventions for different pathways.

Benefits to Collaborators:

- A demonstration of how to break down a complex planning process into more manageable pieces for evaluating, developing, and achieving WQ targets through multiple management pathways.

- A series of structured exercises in a downloadable set of training slides and worksheets, for use by anyone who wants to adapt a similar logic flow for their situation.

Background

As a member agency of the U.S. Coral Reef Task Force (USCRTF), the EPA helps lead interagency efforts to preserve and protect coral reef ecosystems in the U.S. An important aspect of this work is to provide scientific support and engage in cross-agency collaborations with the jurisdictions (states, territories, and freely associated states) that manage coral reefs. The jurisdictions are represented by the All Islands Coral Reef Committee (AIC), which produces an annual Chair's Report (Figure 1) that outlines the work accomplishments and outstanding needs of the jurisdictions for coral reef science and management.

The AIC's 2024 report communicated a call for technical support to address water quality issues affecting corals. Specifically, the jurisdictions requested EPA expertise and assistance with: identifying key water quality (WQ) parameters that negatively impact corals; determining thresholds for associated metrics; and, where appropriate, developing WQ standards that protect coral reef health. In response to this request, the EPA Office of Water (OW) launched an internal project, "Addressing WQ Issues for Corals in the Jurisdictions". This ongoing effort aims to create a structured process for collaborating with jurisdictions to evaluate existing or needed WQ criteria, determine the most impactful management pathways to achieve WQ goals, and draw key insights to inform mitigation and infrastructure conversations.

OW regularly partners with ORD on USCRTF projects, and the Organon was recognized for its potential as an action and decision-making logic cycle that could structure collaborations with the jurisdictions on their water quality issues for coral reefs. The resulting partner project took the form of an intensive two-day working meeting of EPA experts to create a structured flow for tailoring future interactions with the coral reef jurisdictions to assist them with furthering their WQ science and management goals.

Methods

The effort began with several webinars to discuss the Organon (Figure 2) and how it could be used to develop a framework to help the coral reef jurisdictions evaluate the most impactful water quality management pathway(s) to achieve their WQ goals for healthy coral reefs. The chosen approach for framework development was to hold a two-day, in-person working meeting during which the EPA team would run through a series of exercises to break down the complex WQ management process into more manageable pieces. This would be done with a particular jurisdiction in mind—Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI)--and developed as a “training” for eventually working through the process in more detail with CNMI and other jurisdictions. Thus, the goal and scope (Step 1; Figure 2) for the in-person training was defined by the team as follows:

Goal: Help the jurisdictions 1) review current information on priority WQ parameters that negatively impact corals and whether current WQS criteria are protective/needed; 2) evaluate and prioritize regulatory and voluntary pathways for protecting WQ for corals; and 3) engage in action planning to implement pathways interventions.

Scope: Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI).

In preparation for the in-person meeting, team members studied the Organon website and reviewed resources that OW had already collected for CNMI, including information on priority WQ parameters that negatively impact CNMI corals and CNMI’s current (non-coral specific) WQ standards. Building on this, five workshop exercises (Figure 2) were designed for use in evaluating the status of CNMI’s existing information, reviewing what work is already occurring and what is still needed, and examining how work links together holistically among steps to achieve WQ goals for healthy coral reefs. The two days were spent running through the exercises as a practice “training” and using the team’s collective expertise to further improve the exercises for future use with jurisdictions. The five exercises were:

- Exercise 1: Vulnerabilities to WQ Threats at Sites, moves from goal setting (Step 1, established above) to characterizing the vulnerabilities (Step 2) of coral reefs to WQ threats at CNMI sites (Step 3). Steps 2 & 3 are considered together here because location will usually need to be specified to identify the most important WQ threats and their sources. A worksheet was designed to capture details on the WQ threats of concern in CNMI, including their negative effects, interactions with other stressors, specific components of vulnerability (i.e., exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity), and the availability of data or other resources on these topics.

- Exercise 2: WQ Interventions, considers the types of interventions (Step 4) that have been or could be used to mitigate the WQ threats of concern identified in Exercise 1. A worksheet for this exercise was created to compile information on how different interventions work, whether they have been applied in the past and how well they performed, and potential pros and cons of their application to address WQ stressors.

- Exercise 3: Evaluating Pathways to Implementation, uses a flow chart to plot out the transfer of information represented by the arrows between the Planning Triad and the Implementation Triad. For planning to move to implementation, consideration must be given to the type of management pathway—voluntary or regulatory—that could be used based on sources of WQ threats, near/long-term goals, availability of data/monitoring programs, and resource limitations. The flow chart orders the steps needed to follow each of these management pathways, allowing comparison of the types of interventions that could be applied for each, the status of pathway development within the jurisdiction thus far, potential information feedbacks, and data gaps.

- Exercise 4: Second Iteration for Strategic Design, involves a return to Step 4--taking what was learned during evaluation of management pathways—to pursue deeper strategic design of interventions. A worksheet is used to document more detailed design considerations for particular interventions in the context of management pathways under changing environmental conditions.

- Exercise 5: Implementation Support, takes a “white board” approach to sketching out expected needs for the Implementation Triad (Steps 5-7) for each type of management pathway. Looking into the future of how WQ criteria, thresholds and/or standards will be used to implement management interventions is important for both long-term planning and for identifying additional research and planning needs (i.e., further iterations of the Planning Triad).

Results

At the in-person meeting, the Exercise 1 worksheet was used to organize knowledge from the team on specific WQ threats of concern to CNMI corals, along with the impacts and vulnerabilities to those threats, any interacting stressors, and the relevant data or other resources that might be available. Example results for one of these WQ threat parameters (Nitrogen) is shown in Table 1. Exercise 1 results revealed site- and parameter-specific insights about the key vulnerabilities that could inform how those threat parameters should be addressed, as well as gaps in knowledge that might limit action. In particular, the worksheet notes captured information on stressor interactions, variability in stressor effects across sites and species, and other information that could affect considerations of potential interventions in Exercise 2.

The Exercise 2 worksheet was used to consider interventions that could be applied to address vulnerabilities to the threats of concern, using the specifics developed in Exercise 1 to help define the interventions considered. Example results for one of these interventions (reef restoration) is shown in Table 2. As the team documented the details of this and other interventions that could be applied to address WQ concerns in CNMI, they found it particularly valuable to think not only about the mechanism by which the interventions would improve WQ, but also practical considerations and pros and cons that would come into play for implementation. The information collected in this exercise was recognized as a basic screening that could help the jurisdiction by supporting an informed, albeit preliminary, trade-off analysis for decision making.

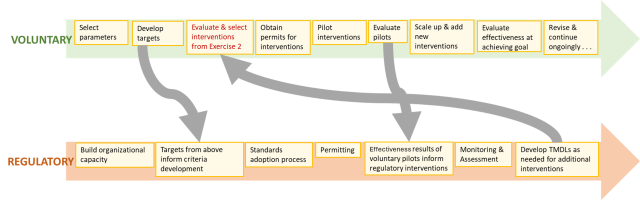

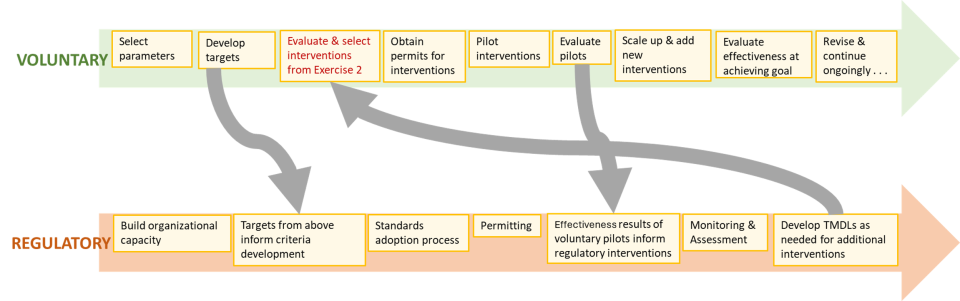

In Exercise 3, the team used a flow chart to lay out a variety of steps needed for implementing water quality interventions along the voluntary and regulatory pathways. An excerpt showing the main elements of implementation for each pathway—and some of the connections between them—is shown in Figure 3. In discussing details of what was needed for each pathway as well as relative benefits, potential limitations, and interactions, participants recognized how activities initiated along the voluntary pathway could either lead to further voluntary steps or inform the activation of more intensive regulatory steps. Choices between the pathways can be made, or both can be followed in tandem, allowing for flexibility in future decisions about how to implement WQ management actions as additional information is gathered over time. For example, a threshold could be developed and used as a voluntary management target rather than a regulatory limit, and as such its initial development can be less restrictive than if developing a WQ criterion. Alternatively, the information could be further refined to develop a regulatory criterion that is legally enforceable, giving more power to drive actions; yet this pathway may require levels of detailed effort and enforcement that may exceed the resources available in some jurisdictions. In either case, interventions identified in Exercise 2 would be designed for use in voluntary programs, and where relevant could later be returned to and adapted for meeting regulatory standards and total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) determined by the regulatory pathway.

In Exercise 4, having a collective understanding of management pathways, the team returned to the Planning Triad (Figure 2) for a second iteration of Step 4. Example results for one intervention (soil stabilization with vegetation) is shown in Table 3. This worksheet delved deeper into more explicit consideration of how the impacts of changing environmental conditions could be taken into account to improve the robustness of intervention designs. Location-specific information, trade-offs, resource availability and limitations, and other practical factors for implementation were also recorded. Workshop participants noted that experts familiar with both biological and engineering design issues, as well as potential local partners, should be engaged for this step when facilitating the framework with the jurisdiction.

In Exercise 5, the team used a ‘white board’ approach to look ahead to what would be needed for the Implementation Triad (Figure 2). Example results for the voluntary pathway are shown in Figure 4. The green ‘sticky notes’ were compiled under the various yellow headings to lay out the types of information, activities, funding, partnerships, and other considerations that would be necessary for the jurisdiction to move ahead with implementation of interventions along chosen pathways. Cost and the capacity needed to be able to implement the identified interventions/pathways were considered paramount to assure that a resulting action plan (Step 5) would be feasible for implementation, monitoring, and evaluation of effectiveness (Steps 6-7).

Outcomes

In this project, the Organon was used by the EPA as an action and decision-making logic cycle, to organize information and develop a framework for working with the coral reef jurisdictions on WQ issues. The team found that running through the exercises in person during a two-day meeting was an effective way to craft an approach that could eventually be used with the jurisdictions. Group discussions revealed valuable insights into the dynamics and applications of each exercise and how they link together to fully complete the Organon cycle. Participants who were new to the Organon process appreciated the flexibility with which the worksheets could be applied when working with various jurisdictions, which may have different levels of expertise or may be starting from different stages in the WQ management process. After the in-person meetings, the team worked to package the slides and worksheets into training materials (see link below) that can be freely accessed and adapted by any user for their situation.

Intended next steps are to present this framework to the USCRTF and begin using the training slides and worksheets with coral reef jurisdictions that have requested technical support in addressing WQ issues that affect corals. The aim is to facilitate the use of a framework and structured approach that can be consistently applied, yet adaptive for tailoring each jurisdiction’s path to effective WQ management for coral reefs.

The USCRTF has a long history of collaborating with non-governmental organizations (NGOs) when providing expertise to jurisdictions. Several NGOs have expressed interest in this framework for other technical applications, such as adapting the series of exercises to structure decisions for research and management of microplastics in the environment.

The structured exercises are available as a downloadable set of training slides and worksheets, for use by anyone who wants to adapt a similar logic flow for their situation. Click the link below for a summary page with links to the slides and worksheets.

Downloadable Training Slides and Worksheets (pdf)

Partner Team

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Office of Water

Katherine Weiler, Office of Wetlands, Oceans, and Watersheds (OWOW)

Nick Rosenau, OWOW

Francis Adams, ORISE Fellow @ EPA

Karen Kesler, Office of Science and Technology

EPA Office of Research and Development (ORD)

Jordan West, Center for Public Health and Environmental Assessment (CPHEA)

Amity Zimmer-Faust, CPHEA

Technical Support

Anna Hamilton, Tetra Tech, Inc.